By

Boniface Okanga & Jennifer Davis-Adesegha

London, England, June 2025

Abstract

What legendary historical businesses do to stay perpetually alive, omnipotent, omniscient, omnipresent, disruptive and revolutionary despite passing through some of the most deadly disruptions in the world’s history, is only the legendary businesses themselves that understand. It is such curiosity that drives this study to analyse the contemporary legendary historical businesses’ behaviours, strategic actions and responses to a series of turbulences from the steam engine era to the modern days of artificial intelligence and machine learning. Through such analysis, the study aims to understand the underlying drivers and secrets of most legendary historical businesses’ survival and transfiguration to evolve from not only one decade to the other, but even from centuries to centuries. Of course, it is difficult for business secrets to be easily revealed. However, from the evaluation of these legendary historical businesses’ behaviours since inception, it was found that as legendary historical businesses emerge just like any other businesses, they often arise from the introduction of a single more revolutionary invention like it was the case for Nestlé’s baby formula, General Electric’s electric light bulb invention, Unilever’s light soap invention, Ford’s automobile’s invention and Walt Disney’s theme and amusement parks. From these single inventions, they create single thriving enterprises, while also analysing and responding to probable changes in industry and market trends. In the event that risks of market saturation are detected in the near future, they diversify to mitigate risks of failure. Even while pursuing diversification, they still remain agile and responsive to constant market changes by engaging in continuous innovation to create and deliver new products that respond to new needs. If changes in industry and market trends become quite volatile to affect any of the diversified ventures, legendary historical businesses are often not afraid or hesitant to proactively disinvest from the loss-making ventures to focus only on the profit-generating ones. In the event of more lethal disruptions, they use the accumulated financial resources to engage in aggressive innovations that disrupt the unfolding disruptive trends and reshape the industry terrain to their favour. But if they cannot do that because they don’t have the required unique talents or technology, they often resort to acquisition of the emerging disruptive businesses. This destroys the emerging disrupters whilst also leveraging their capabilities to access, assimilate and utilize the acquired new talents and technology to revolutionize the industry to their advantage. In all these business transfigurations, strategic succession planning is often part of the essential underlying business strategy, driving the business’ transfiguration, reorientation and evolution from the disruptions in a particular decade to the other, until it perpetually evolves from centuries to centuries, and even into the largely unknown future. From this behavioural analysis, legendary historical businesses were found to always remain legendary across centuries because they are strategic diversifiers, agile operators, continuous innovators, disruption’s disrupters, strategic assimilators, and strategic succession planners. For the contemporary businesses that aspire to remain sustainable and resilient, it is such similar business behaviours that they must emulate if they are to continue thriving up to 2100 and even beyond.

Keywords: Steam Engine; AI; Machine Learning; Legendary Historical Businesses; Disruption; Market Changes

INTRODUCTION

From the heydays of steam engine usage to the modern disruptive era of artificial intelligence and machine learning, the global business environment has seen the emergence of some legendary historical businesses that have experienced and passed through a series of the most disruptive events the business world has ever seen. Yet despite passing through such disruptions, they have still remained legendary, omnipotent, omniscient, omnipresent, disruptive and revolutionary. These instigate questions as to how do they do it? What is the magic bullet for creating, developing and nurturing a business that becomes multinational, sustainable and perpetually revolutionary to surpass generations and generations of all living organisms? When World War II broke out in the 1940s to destroy almost everything, everyone expected Pfizer, a chemical company, later turned a pharmaceutical business entity founded in 1849 in Brooklyn, New York, to play the last instrumental roles of developing, fermenting and supplying the wounded US soldiers and allied forces with penicillin. Instead, after passing through the 1970s’ energy crisis, the protracted American economic depression of the 1970s and the 2008 financial crisis, Pfizer emerged even stronger as a more revolutionary player during the Covid-19 pandemic than it was during the Second World War. Pfizer, in conjunction with the German-based BioNTech, emerged as one of the major frontline players, creating and distributing mRNA vaccine that disrupted and slowed the Covid-19 virus spread and mutation. These released billions of the global population suffocating in a series of various Covid-19 lockdowns.

Yet as the Titanic sank on 15 April 1912, and the world wailed and mourned, as Coca-Cola served its carbonated soft drinks and Anheuser-Busch distributed its various beer brands to the mourners, none of the global mourners imagined that Coca-Cola, founded by Pharmacist Dr. John Stith Pemberton on 8 May 1886 in Atlanta, Georgia, would still be doing the same thing 113 years later. None of the mourners also imagined that Anheuser-Busch, founded in St. Louis, Missouri in 1852, would also still be doing the same thing in 2025. Instead, through continuous innovation influencing its seamless transfiguration, evolution and adaptation to a series of disruptive industry changes, Anheuser-Busch is still doing even better, as it generated $59.768 billion annual revenue and net profit of $7.061 billion in the 2023/2024 financial year. Likewise, when the global population washed and bathed with Unilever’s Sunlight soap in 1885, not even the intellectuals in the 1884–1885 Berlin Conference for the partition of Africa amongst the colonial powers imagined that in 2025, the global consumers would still be using even better Unilever brands like Dove, Axe, Lux and Knorr. But through resilience and the power of continuous innovation, Unilever, just like the other legendary historical businesses, has been able to survive, transfigure and reorient itself to evolve to not only thrive in the 21st Century, but also attain omnipotent, omniscient and omnipresent status across the global markets in which it operates.

Since most businesses fail just a few months or years after establishment, these signify that what legendary historical businesses do to stay perpetually alive, disruptive and revolutionary despite passing through some of the most deadly disruptions of human life, is only the legendary businesses themselves that can understand. When World War I unfolded in 1914–1921, Stora Enso, founded in Sweden in 1288, was already a disruptive copper mining entity operating in Sweden and Finland. Despite the Great Depression of the 1930s, World War II and the 1970s’ Energy Crisis, Stora Enso has still evolved and transfigured from its tiny Swedish operation into a major operator in the global renewable energy, biomaterials and packaging materials industry. Even when Covid-19 proved more lethal, Stora Enso still evolved and remained resilient to generate the annual revenue of €9.049 billion in the 2024/2025 financial year.

Just like Stora Enso, Samsung, which was just selling dried fish and grains in 1938, was expected to have been extinct by now, given the destructive effects of major global disruptions like the Great Depression of the 1930s, a series of Asian earthquakes, World War I, World War II, 2008 Financial Crisis and Covid-19. Instead, Samsung emerged even stronger, evolving and transfiguring from just the South Korean dried fish vendor into a revolutionary innovator and manufacturer of semiconductors, telecommunication equipment and various consumer electronics. Even when Covid-19 dismantled the entire global economic system of the world, Samsung still remained resilient and rebounded even stronger with the annual revenue of $206.7 billion in 2014. This turned into a net profit of $22.47 billion in 2024, a figure that can pay up King Mswati’s Eswatini’s public debt of E35.5 billion ($1.9 billion). Such insights demonstrate how some legendary historical businesses like Samsung seem not only resilient, but also to have certain unique internal systems that insulate them against the frequent disruptive global changes. As legendary historical businesses like Toyota, Coca-Cola, Nestlé, Unilever, General Mills, General Electric and BMW attain undisrupted omnipotent, omniscient and omnipresent status for centuries and centuries, it means what legendary historical businesses do to stay perpetually alive, disruptive and revolutionary despite passing through some of the most deadly disruptions of human life, is only the legendary businesses themselves that can understand. These raise a lot of questions as to how such businesses do it? What are their unique strategies and secrets? It is such questions that this study probes by evaluating and exploring the underlying secrets of legendary businesses’ survival, continuity, sustainability and transfiguration to evolve from the Second Industrial Revolution era to date, and perhaps further deep into the long unknown future of business.

We are now in 2025, the 21st Century and one wonders how businesses which were super players in their respective industries like Stora Enso in 1288, Pfizer in 1849, Unilever in 1885 and Germany’s BASF (Badische Anilin-Soda Fabrik) in 1865, are still even more revolutionary players today. Keeping a business glued to its vision and mission for decades or even centuries and centuries is not an easy task. Some businesses are created without long-term vision and hence if the founder perishes, so also does the business. Others are founded as generators of side incomes aimed at supplementing incomes from the poorly paying jobs. Others to support one during the course of educational pursuits and if education is completed, the business is also abandoned. Others are businesses just started for fun—like Facebook that started among Harvard students in the name of “Facemash” as just a platform for making fun and jokes among students by comparing which students were “hot” or “not”.

While Facemash co-founders thought it was just a joke that would not pass the Harvard gate, Mark Zuckerberg took it seriously. Other businesses are started by parents to keep their children occupied during holidays or to develop, groom and nurture their children as future disruptive entrepreneurs or business leaders. Others establish small businesses just to please their wives, girlfriends, side-dishes, husbands or boyfriends that they also have businesses, only to fail when love also expires. While other businesses are created as the major source of livelihood, especially among the Asian communities, others create businesses because of unemployment and once a job is found, the business is also abandoned. Irrespective of the reasons for creating a business, keeping a business sustainable and resilient against all odds and turbulences for just a few years, let alone for decades and decades or centuries is not a walk in the park. Following the higher failure rates of several emerging businesses around the world, a lot of studies have been conducted in Latin America, Asia, Africa, Asia-Pacific and Eastern Europe to understand the reasons why most emerging new businesses do not take long in the market.

Some studies highlight poor change management that affects adaptability, poor innovation, limited investment in new product development and poor quality management. Others attributed the constantly unstoppable failures of emerging new businesses to poor succession planning, poor planning, lack of funds, political instability and economic depression. Even if these are some of the plausible reasons, it is still difficult to discern why despite such challenges, the likes of Stora Enso, General Mills, Unilever, Toyota, Ford, General Electric, Pfizer and Nestlé, which were disruptive players in the 18th Century, have still retained or improved the vigour to emerge as even the strongest disruptive players in the 21st Century.

It is such curiosity that drives this study to evaluate and explore the underlying drivers of some legendary historical businesses’ sustainability, despite experiencing and undergoing some of the most turbulent disruptions in the world’s history. Using integrative review as a qualitative research method for critical content analysis, this study sought to analyse and discern the underlying drivers and secrets of most legendary historical businesses’ survival and transfiguration to evolve from the steam engine era to the modern days of artificial intelligence and machine learning.

Secrets of Legendary Historical Businesses

From the analysis of legendary historical businesses’ behaviours, strategic actions and responses to a series of various turbulences, it was found that legendary historical businesses often remain legendary across centuries because they are:

- Strategic Diversifiers

- Agile Operators

- Continuous Innovators

- Disruption’s Disrupters

- Strategic Assimilators

- Strategic Succession Planners

Details of how legendary historical businesses behave and act in all these contexts are elucidated as follows.

Strategic Diversifiers

As the case of General Electric indicates, extensive diversification can cause problems of control, higher costs, diseconomies of scale and risk of failure. But even if such problems arise, risks of complete failure and extinction are still minimised. In the event of problems, the business can choose and close the less profit-generating ventures, to focus on the relatively more profitable ones. Diversification creates the foundation for the business to transition to another industry if its existing lucrative one dries up. When GE Capital became dry as a result of inflation and rising interest rates in the US financial market, it was extensive diversification into sectors like renewable energy, healthcare and medical imaging technology that created the foundation for GE to close and abandon GE Capital in favour of GE Energy, Electricals and Healthcare. For Samsung, its creation of Samsung Electronics as it sold dried fish and grains, created the foundation for change, transformation and transfiguration from dried fish vending into telecommunication and consumer electronics’ manufacturing. Diversification enables the business experiment with new sectors before making the decision to shift in order to avoid failure in the existing industries. It is through such initiatives that legendary historical businesses transition from one sector or industry to another. This aids the business’ survival and change into new industries from year to year and decade to decade until it becomes from century to centuries like it is in the cases of General Mills, Unilever, Nestlé, Toyota and Stora-Enso. Diversification is key in the evolution and survival of most legendary historical businesses.

As legendary businesses strive to survive and remain sustainable throughout different phases of market disruptions, diversification becomes essential for mitigating risks of concentrating in just one market. When the 2008 financial crisis disrupted the US financial and mortgage markets, General Electric that had diversified from aircraft engine making, healthcare, electric lighting and energy into the provision of financial services, mortgage and credit card services under its GE Capital had to sell off its GE Capital and other non-profit-generating ventures to focus on only its core businesses. The failure of GE Capital affected GE’s general reputation and brand image, but still it did not take GE out of the global market. This is because General Electric got insulated from failure due to its extensive diversification into various related and unrelated industries. Across the lives of several legendary historical businesses like Samsung, Toyota, Siemens and BASF, it is diversification which is a distinctive business practice. It is among the corporate strategies that have been quite instrumental for leveraging their survival and evolution from one period of failure to the next seasons of superior market performance. As the business diversifies across several related industries and sectors, turbulence affecting the performance of the business in one sector can be insulated by the business’ superior performance in the other markets. This enhances the survival and continuity of the business. Even if its original business concept dries up, the business can still continue with the new businesses created in the other sectors.

However, successful use of diversification as a defining corporate strategy requires the business to extensively invest in innovation as well as R&D (Research and Development). Adoption of an innovative culture improves the capability of the business to improve the existing product features and attributes. It also enhances the creation of new products. In the long run, this aids the business’ use of diversification strategy to undertake horizontal, concentric or conglomerate diversification. For horizontal diversification, the innovation process enhances the creation of new products exhibiting features and attributes analogous to the features and attributes of the existing products. Though the business may have to invest in R&D to emerge with such new product features and attributes, the technology, resources, know-how and machinery for making such products often remain slightly complementary and similar.

Somehow, horizontal diversification is the other alternative strategy of improving the maximum utilisation of the existing production resources and technology in the making of as an array of different products as possible. When Apple applied horizontal diversification strategy into the making and sale of its Apple Watch, it used similar and complementary technology, equipment, know-how and resources that it uses for making iPhone. This increases economies of scale to reduce marginal costs of producing additional units of output. Yet as it does that, horizontal diversification also spurs increment of operating and net profit margins. Diversification is a strategic key for leveraging a business’ sustainability. If one of the created related businesses fails, the business can still rely on the other thriving business ventures.

However, concentric diversification is not the same as horizontal diversification. Usage of concentric diversification requires the business to create new business products that are closely associated with the existing products in terms of the required know-how, technology, equipment, market and resources. Concentric and horizontal diversification strategies aim to improve the business’ effective performance in the existing and related markets. This contrasts with the approach in conglomerate diversification that takes the business away from the existing market and industry to explore the opportunities in completely unrelated markets and industries. Conglomerate diversification is quite costly, but it often pays back enormously. In case of complete failure in one market, the business can still survive because of its operation in the market which is completely not affected by the turbulence in the existing one. It is this style of business operation and management that has been the secret of most of the legendary historical businesses.

As most of the legendary historical businesses evolved from as far back as 1929 up to date, and even further counting into the future, it is diversification which has been part of the unique strategies influencing their successful evolution and transformation from one period of disrupted market performance to the other. Combined with the application of other strategies like strategic acquisitions, the perfect case of how successful corporate diversification influences the growth, sustainability, survival, transfiguration and evolution of most legendary historical businesses is reflected in the case of Stora-Enso. Stora-Enso is the world’s oldest business, founded as a copper mining company in Sweden in 1288. With headquarters in Stockholm–Sweden and Helsinki–Finland, Stora-Enso was previously just a copper mining company. But as time evolved, it realised that copper was not generating the desired revenues due to the beginning of copper deposit’s continuous depletion. This prompted the creation of other business ventures dealing with ironworks and paper production. In the 1800s, this arose from Stora-Enso’s analysis of how its business could gain from Sweden’s unexploited vast forests of the 1800s. However, as stringent global environmental laws emerged, Stora-Enso shifted its business model from engagement in direct paper production to developing, manufacturing and selling recyclable packaging products, bio-based polymers, wood-based textiles and carbon-neutral construction materials as well as renewable energy. Due to the power of diversification, Stora-Enso has been able to survive from 1288 to 2025, the era of artificial intelligence and machine learning.

Of course, with diversification accompanied by some analysis and response to changing market landscapes by creating new businesses, Stora-Enso now has footprints across Asia, Europe, Latin America and the US. While passing through all the turbulences associated with all the four industrial revolutions, Stora-Enso now generates annual revenue of 9.049 million euros. Yet as Stora-Enso was dealing in copper mining, Samsung, the renowned global consumer electronics’ maker and vendor of today, was a processor and vendor of dried fish and grain in 1938. Created and established in Daegu–South Korea by Lee Byung-Chul, Samsung was processing and selling dried fish, grains, noodles and groceries in 1938 without any idea that it would end up as the maker and vendor of revolutionary smartphones of the 21st Century. Though Samsung remained in this business for a relatively long period, it began diversifying into food processing, textiles, insurance and retail as well as the making of black and white TVs, radios, washing machines and refrigerators in the 1950s. In the 1970s, it further diversified into the manufacturing of semiconductors, home electronics and telecommunication equipment.

Samsung’s food processing remained viable, but as trends like technological advancements and consumer preferences shifted in favour of consumer electronics, Samsung saw the importance of refocusing its energy on the development and manufacturing of more semiconductors and other consumer electronics products for sale to the US. After World War II, the global population was interested in following and tracking the events leading to the complete end of the war. In the 1950s, this spurred the increase in the demand for radios and TVs. Other factors were attributable to stronger support by the South Korean government for the development of import substitution industries and the successes of the likes of Panasonic and Sony in Japan. These trends prompted Samsung to commit more resources to gain the global footprint as one of the leading operators in the global telecommunication and consumer electronics segment.

Though Samsung has today shifted from food processing to consumer electronics where it sees more growth opportunities, it still remains a diversified company holding the division for consumer electronics and mobile devices, as well as the segment for manufacturing semiconductors and its other associated technologies. From selling dried fish in 1938 to 2025, these illustrate how diversification enhances a business’ capability to explore new growth opportunities in new industries without necessarily leaving its present industry. With an annual 2024’s revenue of $206 billion and operating profit of $22.47 billion, which can remain even after financing Kagame’s 2024/5 Rwanda budget of $5.01 billion (RWF 7.03 trillion), this signifies it is through diversification that businesses are able to transfigure and evolve from one disruptive period to the next.

Diversification enables businesses evaluate and respond to the unfolding trends by creating and experimenting new ventures without abandoning their current businesses. If the experiment is successful, Samsung’s practice implies they begin to gradually shift and abandon their previous businesses to focus on the new growth-leveraging entities. With time, this bolsters a business’ change, transformation and evolution from one decade or even century to another.

To survive, this means the business must keep on diversifying and diversifying for as long as trends change and the business remains in existence. In some instances, diversification into a new industry may not be a success. If it is not successful, it implies the business must take agile actions to quickly change and come up with new business insights to survive. Unfortunately, some of the legendary businesses have not been good at doing that, while the others have been relatively very successful. The case in point is reflected in the American Savings and Loans. American Savings and Loans was almost a social enterprise created in the 1800s to tap business opportunities arising from facilitating ordinary low-income Americans to access home mortgage. To achieve that, American Savings and Loans introduced not only deposit savings, but also long-term fixed mortgage loans. To entice ordinary Americans to consider saving with American Savings and Loans, it introduced relatively higher interest rates for deposits and lower interest for its mortgage loans. This is a strategy that would turn out in the future to frustrate its success.

However, with American Savings and Loans in operation, the boom came in the post–World War II period, when families disintegrated were reuniting and ex-servicemen returning from war wanted peaceful homes for rest and reflection. Combined with the US government’s GI Bill that provided financial assistance and support to veterans and more stable interest rates, this caused a surge in demand for housing. However, the legacy commercial banks were not able to help due to the stringent credit requirements that most ordinary Americans were unable to meet. It is this misfortune that American Savings and Loans turned into fortunes. Using these prevailing business opportunities, American Savings and Loans took the opportunities to grow. As it exhausted all the existing houses, it diversified into the construction and selling of its own houses using its existing mortgage systems. Using such a strategy, American Savings and Loans’ growth continued its upward trajectory.

However, in the 1970s to 1980s, challenges soon arose. Rising inflation prompted the Federal Reserve Bank to increase interest rates to curb down inflation and constant price rises. From these economic changes, American Savings and Loans found itself starting to struggle to maintain multitudes of long-term-low-interest mortgages that were not generating a lot of profits. Even with limited profits, it still had to pay higher interest rates on deposits in order to retain the existing depositors whilst also attracting new ones. This caused a mismatch that made American Savings and Loans lose a lot of money. Yet as it was struggling with such challenges, during the height of its growth, American Savings and Loans had also diversified into the construction and mortgaging of its own residential and commercial real estates. Due to inflation and rising interest rates, this was a mistake as rising interest rates and inflation caused the general increase of construction and building materials’ costs. This left American Savings and Loans constructing its houses at higher prices and mortgaging them at lower interest rates that could even take longer to be paid up. The end result was that American Savings and Loans started to experience liquidity issues. These liquidity issues mutated with the other challenges like declining public reputation and brand image as well as new stringent controls on financial institutions to cause its failure and liquidation. Unfortunately, as failure started to loom, American Savings and Loans did not act with the requisite agility to take actions and avoid failure like the other legendary historical businesses such as General Electric and Nestlé have often done.

Agile Operators

Agility is one of the strategies that legendary historical businesses use for staying ahead of rivals. It is the same strategy that they use to analyse, sense and react to situations by making the required changes to adapt before they are disrupted by the emerging new trends. Agility is part of the change management process. It is through adoption of agile business operation that legendary historical businesses have been able to stay alive and shift during one period of turbulence to the other. Agile business operations enable a business take actions to change and adapt even before changes occur. After the death of Walt Disney in 1966, Roy Disney and the team realized that if they did not take quicker actions to address the looming failure, it would be difficult for Walt Disney Company to easily rebound back with the vigour that it had prior to Walt Disney’s death. Walt Disney had been the founder, leader, innovator, visionary and inspiring transformational leader who spurred higher investor confidence just like customer confidence. Immediately after his death, which can be considered an internal business change, Walt Disney Company started to realize declining sales, stagnated innovation and growth. The company was just in the maintenance mode as the remaining business leaders led by Roy Disney focused on maintaining what had remained, instead of pursuing innovation and the search of new ideas for innovation, expansion and growth. This caused declining sales and eroded investor confidence and trust. Realizing that these were symptoms of the impending major failures, Roy Disney, who had postponed his retirement, worked with Michael Eisner, the new CEO, and Frank Wells, the new Walt Disney President, to launch a combination of aggressive corporate restructuring, brand revitalization, innovative initiatives, expansionist approach, diversification and cost control initiatives that came to be dubbed as “The Disney Renaissance of the 1980s.”

Through the implementation of its Disney Renaissance strategies, Disney rebounded back with stronger innovation outcomes influencing significantly improved financial performance. Disney increased its R&D investment to spur improved creativity and innovation, introducing more improved animated movie hits like Beauty and the Beast, The Lion King, The Little Mermaid and Aladdin. With new hits, Disney adopted novel marketing and promotional strategies that marketed, rebranded and repositioned Disney as even better than the way it was before Walt Disney’s death. This revitalized investors’ confidence and sent destructive signals to competitors that Disney was a business bigger than its founder.

To gain new capabilities that improve its competitiveness, Disney acquired Marvel in 1990 to access the superhero market. It acquired Pixar in 2006 to improve its innovative animation capabilities, and did the same to Lucasfilm in 2012 to gain access to the Star Wars franchise. Combined with Disney’s recent acquisition of 21st Century Fox in 2019, these insights illustrate how agility is pivotal in the initiatives influencing the evolution of legendary historical businesses from the steam engine era to the modern artificial intelligence age. Unlike Disney that became agile after it had tasted risk of failure, Unilever is a business which is organically run using a more proactive approach aimed at identifying and thwarting risks before they affect its business operation. Agility is at the heart of Unilever’s business operation. Agility has improved the ability of Unilever to survive and thrive from the years of its establishment in 1929 up to this modern era of artificial intelligence and machine learning.

Founded in 1929 after the merger of United Kingdom’s Lever Brothers, which was mainly a soap manufacturer, and Netherlands’ Margarine Unie, which was a fats and margarine manufacturer, Unilever has transfigured to evolve into a leading global conglomerate focusing on manufacturing, distributing and selling consumer goods like food, beauty, personal care and home care. In all these, the adoption of agile business operational philosophy has been the driver of its innovativeness, adaptability and resilience in the face of all adversity. These have enabled Unilever to create the persistently leading brands like Lipton, Magnum, Dove, Hellmann’s and Knorr to stay ahead of its rivals. However, realizing that its sole reliance on soap and margarine manufacturing is a risky unsustainable business approach, Unilever invested in aggressive innovation leading to diversification into the internal development and manufacturing of detergents, personal care products, tea and ice cream. To achieve that, Unilever acquired powerful brands like Lux, Lifebuoy and Dove and ice cream brands like Magnum to improve its innovative and manufacturing capabilities. Realizing how the increasing concerns of the global communities about environmental wellbeing can affect Unilever’s future business operation around the world, it acquired Seventh Generation, which had invested enormously in the development of eco-friendly cleaning materials. It acquired Ben & Jerry’s, which was more successful in the manufacturing and sale of ethical ice cream.

Unilever introduced its “Unilever Sustainable Living Plan” in 2010 to emphasise the integration of sustainable sourcing, reduction of environmental impact, nutrition improvement and emission reductions in its core business planning and operations. Through these strategic initiatives, Unilever has been able to proactively avoid incidents, risks and scandals that could have affected its effective performance. Realising that digital waves introducing advanced forms of digital operations as supported by the use of artificial intelligence and machine learning technologies would disrupt its seamless business operation, Unilever embarked on an aggressive digitisation initiative. This has integrated digital approach and analytics usage throughout its supply and value chain systems.

Combined with its constant new products’ development, these have improved Unilever’s capabilities to respond to the unfolding new changes in consumer demands and preferences. Throughout its business life-cycle, these agile business approaches have bolstered Unilever’s change, adaptation and evolution against all the emerging new disruptive trends from 1929 to this era of artificial intelligence and machine learning. As innovative behaviours of legendary historical businesses indicate, businesses adopting the agile business operational philosophy never wait for failure. They don’t wait for failure. Instead, they continue evaluating and exploring all the opportunities and the disruptive trends that may emerge from the existing markets. For businesses using agile business approach, even constantly increasing sales is often a cause for worry just like the constantly declining sales.

Constant increment of sales as punctuated with better market performance may cause worries as higher performance attracts the attention of competitors. It puts the high-performing business in the spotlight with the effect that all the emerging new rivals and the existing ones will strive to do just like that higher-performing business, or even to do better. This causes pressure that the high-performing business organisations must deal with if it is to thrive. Just like high-performing businesses, the emergence of symptoms of poor performance may also cause worries and pressure for the executives and managers to deal with the situations. In effect, whether or not the business is doing well, the embracement of agile business operational philosophy requires businesses to constantly be on the lookout for risks of disruptions. Even if the business is constantly doing well, usage of agile business philosophy requires managers to explore additional ways of doing even better to thwart all the identified and the yet unidentifiable risks. This requires constant proactive analysis and innovation. In such endeavours, continuous innovation becomes a proactive business initiative that does not wait for customers to talk. Such behaviours are reflected in the activities of legendary businesses that do not wait for failure. They never wait for customers to complain or talk. They act to ensure that whatever customers or competitors are thinking are addressed before customers or competitors mention them.

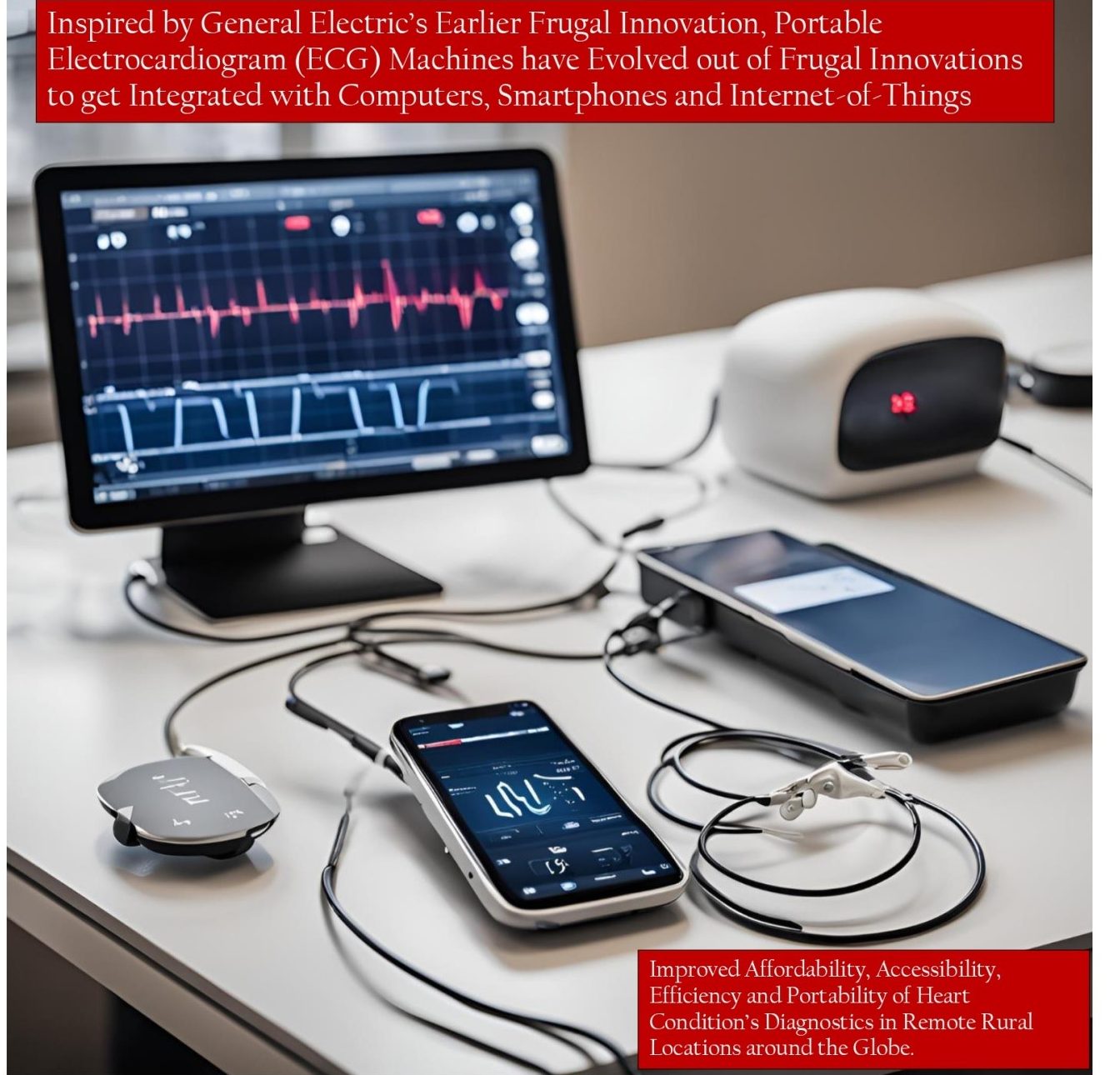

Embracement of such agile business approach has been quite instrumental for influencing the growth, sustainability and survival of Nestlé as a disruptive operator in the milk-based infant formula, condensed milk and frozen food from the period of its establishment in 1867 to the modern era of artificial intelligence and machine learning. Nestlé, that evolved into a major global player, was founded by Henri Nestlé, a Switzerland-based pharmacist in 1867. While running his pharmaceutical businesses, Henri Nestlé discovered the increasing demand for non-breast milk due to the growing number of babies who did not have breast milk for a number of reasons. In response to such demand, Henri Nestlé, a trained pharmacist, did not explore the development of a medical drug that would solve such a problem. Instead, using his pharmaceutical knowledge, experience and talents, Henri Nestlé mixed sugar, wheat flour, cow’s milk and of course some other undisclosed ingredients to create a baby formula which he called Farine Lactée. Farine Lactée, the invented milk-based infant formula, became an instant success and preference for babies whose mothers did not have breast milk or could not breastfeed for one reason or another. It is from the success of this baby formula that the concept of Nestlé as a business was created and established in 1875 in Vevey, Switzerland. Following the increase in its sales and production, Nestlé started exporting to Britain and Germany and then subsequently across Europe. However, with the baby formula milk-based concept becoming very successful, the culture of agility slowly crept into Nestlé’s business operational culture and philosophy. Without waiting for the milk-based baby formula to wane, Nestlé diversified into the production of condensed milk. To improve its capabilities, it acquired Anglo-Swiss Condensed Milk Company to emerge as one of the major operators in the global condensed milk market. Nestlé’s diversification initiatives as a strategy for mitigating risks of failure further continued into the production of chocolate, sweets, biscuits and subsequently the introduction of Nescafé instant coffee in 1938. Even with all this more diversified venture, Nestlé was not satisfied as it introduced canned foods and cosmetics to further mitigate risks of relying on just one or two business ventures.

Nestlé acquired Crosse & Blackwell as well as Libby’s to improve its canned and frozen food development and manufacturing capabilities. However, as consumer preferences started shifting to the consumption of healthier diets and foods, Nestlé did not wait for the changes to become destructive. Instead, it introduced more healthier food diets. It introduced functional foods, dietary supplements and vitamin products to respond to the needs of the increasingly health-conscious global consumers. Nestlé acquired Gerber Products in 2007, Nespresso in 2010, Bountiful Company and Atrium Innovations to improve its functional food production. After selling off its confectionaries—Smarties and KitKat—Nestlé increased the scale of its investment in the production of functional foods and plant-based foods. To achieve that, it introduced brands like Sweet Earth and Garden Gourmet to respond to the growing needs of vegetarians and health-conscious consumers. This agile approach enabled Nestlé to counter the growing competition threats from the likes of Plant-Based Meat Inc as well as Whole-Foods Original. When Nestlé was accused of deceptive advertisement that its baby formula was a complete substitute for breast milk, Nestlé responded by adopting responsible marketing and more corporate social responsibility initiatives before the advocated Nestlé products’ boycott could become a destructive reality. These were accompanied with the adoption of more aggressive business sustainability initiatives to respond to the increasingly stringent environmental laws. These demonstrate how, ranging from the changes in the political trends, consumer demands, health-conscious needs and environmental concerns, legendary historical businesses often take proactive actions to ensure that they avoid being destroyed by such forces of disruptive change. In that process, they also become continuous innovators that create and deliver new products to respond to the changing trends before they become lethal and disruptive.

Continuous Innovators

Legendary historical businesses survive from one period of disruptions to the next because they are continuous innovators. Continuous innovation is often part of the essential business etiquette that has been instrumental for influencing the survival, growth, evolution, adaptability and sustainability of most of the historical businesses. Businesses that adopt continuous innovation as part of the normal business etiquette are most likely to survive and sail for several years as compared to the businesses that do not do so. Continuous innovation improves the capabilities of businesses to continuously analyse, identify and respond to signals of market turbulences and failure. Even without easily identifiable risks of failure, the adoption of continuous innovation culture spurs businesses to read, decode and interpret the implications of the dimensions that the changes in market trends are most likely to take. This enables a business take the initiative to make the required product, service, process, leadership, operational and strategy changes and modifications before they are forced by the impending changes to do so. For Adidas AG to reach, attract and retain more consumers, it had to improve the quality, features and attributes of its sportswear and apparel, while also introducing and integrating more effective digital technologies to improve its operational efficiency. Adidas AG, using Parley Partnership, introduced sports shoes made from ocean plastic. It also partnered, collaborated and engaged with the celebrities and reputable fashion designers to advertise and improve the Adidas brand’s recognition and recall.

While doing this, Adidas AG introduced digital operations to complement and support its physical-store operations. This improved Adidas AG’s evolution as one of the legendary historical businesses from the age of changing customer needs and digitisation to the modern era of artificial intelligence and machine learning. These indicate how continuous innovation is a critical driver of a business’ success, continuity, sustainability, adaptability and evolution from one wave of discontinuities to the other. Continuous innovation leverages a firm’s sustainability. It aids the review of the existing products, customers and services. This enables modifications and adjustments that improve product attributes to respond to the changing market needs. Continuous innovation enables a business not only review and modify the existing products. Instead, when embraced as part of the organisational culture, continuous innovation also enables the review and modifications of the existing operational processes, methods, systems, culture and business philosophy. These changes improve a business’ capabilities to assimilate, adapt and evolve with the unfolding disruptive changes. Changes of the existing product features and attributes enable the business to evaluate and assimilate new market insights.

Even if new insights could have disrupted a firm’s performance, thorough market analysis undertaken as part of continuous innovation and improvement initiatives enhances identification and assimilation of such new emerging disruptive insights. This improves a firm’s agility to adapt and mitigate risks of failure before changes in market trends become devastating. Continuous innovation and improvement are essential for bolstering a firm’s competitiveness. Even if the business is doing well, continuous innovation adopted as part of the organisational culture often drives the business to analyse and improve product attributes even if customers have not expressed dissatisfactions. When DHL (Deutsche Post) Group realised that the emerging new rivals were embracing digital technologies to improve their operational efficiency, it also did the same, even before its customers could start complaining. DHL increased the scale of its investment in Internet-of-Things (IoT), robotics and automated warehouses as part of its digital transformation process. Since DHL is a critical partner of most e-commerce operators, this improved its ability to handle more volumes of logistics’ movement, as instigated by a surge of online trade. DHL responded to clients’ needs for more efficient, convenient and cost-effective global delivery services. It also responded to the increasing global concerns for a healthy ecological environment by introducing electric delivery fleets under its “Green Logistics Initiative”.

For legendary historical businesses, it is often such minor incremental improvements that aid their continuous seamless evolution and transformation from one disruptive period to the other. Continuous innovation is a business philosophy that requires business executives not to wait for failure. Businesses adopting continuous innovation business philosophy do not wait for failure. Instead, they are constantly on the lookout, conducting analysis and asking difficult questions as to whether they are doing the best to satisfy their existing customers. They go at length asking whether their customers are actually pretending or genuinely satisfied. Continuous innovation business philosophy influences business managers to continuously worry about business sustainability. It causes business executives to continuously be worried about the risks and consequences of bad decisions instigating risks of poor performance or failure. In the event of frequent minor customer complaints, businesses subscribing to continuous innovation culture are often fast and agile to address issues raised in customer complaints. Such business approach prompts the creation of an effective platform for receiving and responding to customer complaints.

Usage of a more structured customer complaints’ management system improves the effectiveness of the analysis and response to the areas of dissatisfaction. Effective response to customer complaints sends signals to customers about how the business executives value and take their businesses seriously. Failure to effectively respond and address customer complaints often sends a signal that the business does not only care much about customers, but also its business’ wellbeing. In response to safety and customer complaints about some of its cars, Toyota has gained significant reputation, trust and confidence for acknowledging faults and recalling its cars from the entire global market. In sort of a strategic move which is sometimes used as a marketing and promotional stand depicting Toyota as a resourceful multinational that can withstand enormous losses by recalling millions of defective cars, Toyota recalled in the period between 2009 and 2020, 8.5 million vehicles.

The recalled defective vehicles included Toyota Corolla, Camry, RAV4, Prius and Lexus for defective unintended accelerations. To correct the error, it halted production and redesigned the floor mats and pedal systems and introduced changes in the braking software systems. With the unintended consequences of sending signals to rivals about Toyota’s financial capability, Toyota spent $42 billion on the required corrections, while also paying $1.2 billion as fine to the US Department of Justice. In another incident, Toyota recalled its cars over the defective power window switch that could short-circuit and cause fire. It also did the same for the defective airbag inflators that could explode, defective rear seatbelt that could be cut by cushion ring during accident crash, as well as the faulty fuel pump that could fail to stall the engine while driving. When loose hub bolts in its first electric car—Toyota bZ4X—could cause its wheels to detach, Toyota not only recalled, but also offered to buy the vehicles or provide incentives to all the affected owners. This demonstrates how Toyota takes its business quite seriously.

Since Toyota has done that for a long time, it is such similar business approach that has emerged as part of its operational culture influencing its improved competitiveness. This higher competitive edge has translated into positive business outcomes influencing Toyota’s evolution and survival from the heydays of 28 August 1937 to the modern era of artificial intelligence and machine learning. Failure to respond to customer complaints can send a signal that the business does not care much about how it does business. Once such a signal is decoded by the customers, it can be interpreted as some of the underlying attitudes explaining why a business may not be bothered about providing better quality products. If customers have doubts about product quality, no matter how it is coated as of good quality, that declining customer confidence and trust may affect competitiveness. What customers are saying about the business should often be the first instigator of innovation leading to the introduction of new product features. It should spur new research leading to the development of new products. Customer complaints reveal new insights that can turn valuable for continuous improvement.

Unfortunately, that is often not the case for most businesses. Most businesses treat customer complaints as burdening and costly to respond to and manage. Yet, customer complaints may reveal new insights depicting what the competitors are offering. It can highlight some novel imagination from the customers that can turn into a source of novel ideas that the business can utilize to create new points-of-difference that bolster its overall competitiveness. When Blockbuster constantly ignored customer complaints for limited movie options and excessively higher late payment fees, it did not take long before Netflix emerged as a rival addressing such complaints. Likewise, Nokia ignored customer complaints about its outdated operating system, poor smartphone features and poor app ecosystem until Nokia was completely overshadowed by Apple and Samsung’s new offering for better smartphones. For Sears, customers complained about its lack of e-commerce platform to improve the convenience of shopping, lack of modernization and poor in-store experience, but it did nothing. Sears attempted to make adjustments when sales started to decline following the emergence of several e-commerce platforms, but it was too late before it filed for bankruptcy in 2008. For Toys “R” Us, it ignored customer complaints for outdated stores, unresponsive pricing and weak online presence only to fail when its failure to act became the cause of failure. These cases of failure suggest continuous innovation requires the adoption of an open-mind approach. How customers are interacting with the product, in-store facilities, staff and management must be thoroughly analysed and interpreted to decode all the signals that the customer could be sending. Even if the product is tested and liked by customers across various market segments, open-minded businesses will often aspire to create and offer the best. They will always keep asking questions signalling lack of trust and confidence in their products.

To improve product quality and features, businesses adhering to continuous business improvement philosophy often avoid complacency arising from the trust and confidence that the business has in its products or services. In continuous business improvement culture, business executives and chief executive officers will always say, “We trust our product. No competitor can beat us”, but deep inside their “minds”, “hearts” or whatever you may call it, they are usually aware that products wane and vanish from the market when customer preferences change. They are usually aware that as the product performs well, there are also competitors that are seeking to do the best to displace the product from the market.

CEOs are also usually aware that due to technological changes or the continuous evolution of society, sudden market changes can also introduce new changes shifting customer preferences in favour of rival products. If businesses have such thinking and understanding at the back of their minds; it often becomes easier for them to embrace a culture of continuous improvement. When Tesla developed a successful Roadster and Model S in 2012, BMW quickly realized that the success of electric vehicles would be the best way forward for most car makers. It predicted the rising cost of fuel, as accompanied with the increasing global demand for clean energy to further drive the increment in electric vehicle demand. In response, BMW introduced its first electric cars—BMW i8 and BMW i3 in 2013. It also modified its production facilities and technologies to introduce flexible production systems producing hybrid, ICE and electric vehicles using the same production lines. This has positioned BMW to respond to the demand for electric cars which is expected to continue surging up to 2100. This demonstrates how in the quest to survive for as long as possible, legendary historical businesses often turn into continuous innovators who strive and aspire to improve, create and offer the best products that meet or even surpass customer expectations.

Legendary historical businesses strive to continuously review and improve the attributes of the existing products. This bolsters their evolution from the unforgettable disruptions in one century to the next century or even centuries. Embracement of a culture of continuous improvement puts businesses under pressure to continuously think and rethink to create, re-create and deliver the best products or services. This improves the adaptability and sustainable evolution of the business from one state of disruptive operation to the next waves of discontinuities. Instead of being disrupted by discontinuities, they look for opportunities that can be exploited in the unfolding discontinuities. Instead of being disrupted by threats, legendary businesses instead turn into disrupters of threats.

Disruption’s Disrupters

Legendary businesses are disrupters of disruption due to the power of continuous innovation and improvement. They convert disruption into novel revenue-generating opportunities. Continuous innovation and improvement influence capabilities of legendary businesses to disrupt threats. It is such capabilities that have often influenced the evolution of some historically disruptive businesses like Ford, General Electric, Siemens, Coca-Cola, Nestlé, General Mills, Schneider Electric, Toyota, BASF and IBM. Some of these revolutionary businesses have been in business since the Second Industrial Revolution, passing some of the most disruptive turbulences instigated by a series of various economic depressions, Cold War that polarized the global market, technological advancements, First and Second World Wars, and globalization. Despite these turbulences, these businesses managed to survive and sail through up to the present date due to the power and influence of continuous innovation and improvement. During periods of turbulence, continuous innovation provokes businesses to think and rethink to emerge with new innovative initiatives of working and thriving through the turbulence. When World War I and II broke out to disrupt the entire global business ecosystem, General Electric shifted its focus from the disrupted private market to exploring multitudes of contracts being offered by the US government. Prior to the wars, General Electric, that had developed a higher level of superiority in aviation and electronics engineering, shifted its attention to reaping a lot from the US government contracts for the development of various military aviation equipment and engines. Because the US Army needed the best aviation equipment to win the war, General Electric did not use only its existing knowledge. Instead, it sought to use the larger amounts of the provided billions of dollars to re-evaluate and improve their existing competencies to develop the best products for the US military.

Circumstances necessitated the importance for General Electric to undertake improvement if it was to meet and respond to its clients’ needs. It is such continuous improvement from the previous aviation products that led to General Electric’s introduction of turbo-superchargers. Turbo-superchargers improved the capabilities of the US military aircrafts to carry more heavy loads as compared to the other enemy aircrafts. As General Electric advanced its turbo-supercharger technology, it also took advantage of the multi-million contracts that it had won to invest in research and continuous improvement of technology leading to the invention of America’s first jet engine, while also modifying and improving its radio technology. Just like General Electric, during the Great World Economic Depression of 1929 to 1939, some historical businesses like General Motors (GM), Sears, Roebuck & Co, as well as Warner Bros, realized that if they were to survive and avoid failure during the Great Depression, review, change, modification and improvement of their business models, operational approaches and strategies were of significant importance. In the move that implies continuous innovation does not just deal with the addition of new features, but also reduction of the offered features, General Motors introduced more flexible production approaches.

These flexible production approaches lowered costs to enable General Motors produce and sell a range of its cars at relatively affordable prices. This improved General Motors’ price competitiveness in the global market where consumers were struggling to make ends meet. To further increase its sales and revenue from the increasingly less attractive American market, General Motors introduced the complementary innovative consumer financing model. This financing model enabled American consumers to purchase GM cars on credit and pay up using installments as time unfolds. It was this model that emerged as the modern vehicle financing system embraced by most of the modern financial institutions. Embracement of a culture of continuous innovation and improvement enables a business read and respond to market signals before failure becomes quite imminent. As GM introduced more affordable cars during the Great Depression, Sears, Roebuck & Co introduced the first Mail-Order Business Model. During the Great Depression, it was even difficult for most rural consumers to afford transport to travel from their rural settings to the stores in the urban areas. Given such challenges, Sears, Roebuck & Co introduced the first Mail-Order Business Model that would require rural consumers to place orders and have the products shipped to their addresses. This model perfectly responded to the needs of rural consumers to spur Sears’ effective performance, growth and sustainability during and after the Great Depression. Though Sears later failed due to failure to adapt to the changing market trends, it was this Mail-Order Business Model that was adopted by the likes of Blockbuster mailing DVDs, before the concept metamorphosed into the foundation creating the modern e-commerce concept adopted by the likes of Amazon and Alibaba.

Such insights insinuate how continuous innovation and improvement require a higher level of imagination and creativity that not only respond, but also surpass customer expectations. It requires businesses to imagine and think for the customers as to what the market requires even if no real meaningful data exists. This is reflected in the fact that as Sears emerged with the more disruptive Mail-Order Business Model that had not been imagined by customers before, Warner Bros introduced low-budget gangster films and music products. These enabled the psychologically depressed consumers to escape the psychological torture and pain of the Great Depression by listening to a variety of musicals or watching the easily affordable and available multitudes of entertaining gangster movies. That was in the Great Depression of the 1930s, but when Covid-19 occurred in 2019-2022, Warner Bros’ 1930s’ approach offered some insights on how Netflix would approach its film and music streaming operations. To respond to the needs of billions of consumers locked up in their homes around the world, Netflix modified its server capacity to accommodate more subscribers and improve user experience. It also spaced out its content releases in the way that would accommodate the halted production, whilst also leveraging its international contents like Spain’s “Money Heist” and South Korea’s “Kingdom” to keep the international audience engaged. In addition to introducing remote work and virtual production to keep its streaming operations moving forward, Netflix also introduced low-cost plans and mobile-only services in emerging markets to increase the number of subscribers. However, these insights do not imply continuous innovation and improvement apply only during turbulences caused by wars, economic depressions or natural disasters. Instead, it also implies continuous innovation and improvement are proactive strategies that do not require turbulences or risks of failure to become quite imminent before businesses can act. To survive the most volatile turbulences, the emerging changes may also require businesses to undertake strategic assimilations of new capabilities.

Strategic Assimilators

Strategic assimilation is one of the strategies that legendary historical businesses use to gain competitive edge, destroy rivals and attain sustainable growth from one state of disruption to the next. In the event of the emergence of disruptive innovations, incumbent businesses often attempt to undertake all innovative initiatives that counter the emerging threats. They will usually seek to change and modify the features of their existing products to outwit competitive forces. They may also seek to develop and introduce new products or operational methods and customer services to counter the emerging new competition forces. If they cannot succeed in disadvantaging the emerging new rivals, then the use of strategic assimilation is often the option. Strategic assimilation refers to the strategic process through which the existing market incumbents acquire the emerging best performing new rival businesses. It is the strategy through which the dominant market players or those seeking to become dominant market players, acquire and assimilate and integrate rivals’ capabilities to bolster the improvement of their overall effective market performance.

Though it is acquisitions and mergers which are commonly used, strategic assimilation may also entail the use of strategic alliances, partnership or just cooperation between rivals aiming at reshaping the nature of the competition game to their advantage. In the event where the incumbent businesses have failed to disrupt the emerging new disruptive market forces, it is strategic assimilation which is usually used as the strategy for acquiring new capabilities. As the incumbent acquires and merges with its emerging disrupters, it gains access to unique talents, resources, technology, experience and business insights that it could not have accessed without strategic alliance or mergers and acquisitions. Strategic assimilation even opens a new market base for all the parties in the strategic assimilation initiative. For that reason, strategic assimilation is commonly used by the modern legendary historical businesses as the tactic for reducing competition heat, accessing new technology, creating new products for new market segments and as the tool for accessing new customer base. Strategic assimilation also enables legendary historical businesses to access newer skills and technologies. This improves capabilities to create novel products that respond to the changing customer needs and demands. When Instagram emerged as a disruptive mobile-photo sharing app, Facebook (Meta) tried all it could by improving the quality, features and attributes of its social media services to attract younger social media users, but still it failed. Instagram seemed to be offering the best easy way to use mobile system for sharing photos. To effectively counter Instagram’s threats, Facebook acquired Instagram for $1 Billion to diffuse threats of future extinction. As this prolonged Facebook’s lifespan as part of the legendary historical businesses’ strategies, Facebook did not rest as WhatsApp became another threat that it had to deal with if it was to survive.

WhatsApp dominated the Asian, European and Latin American markets where Facebook Messenger had not yet become quite popular. This affected Facebook’s growth and expansion across such markets. To deal with such threats, Facebook had to provide an irresistible offer of $19 Billion to acquire WhatsApp. Whereas the acquisition of WhatsApp strengthened Facebook’s messaging infrastructure and capabilities, Instagram became Facebook’s major revenue generator because of increasing user engagement and advertisements. Though Facebook is now being accused by the US Federal Trade Commission for engaging in anti-competition behaviours, its approach still reflects how legendary historical businesses use strategic assimilation as a strategy for acquiring new capabilities that bolster their growth and survival throughout the different periods of acute market disruptions. Amazon is one of the legendary historical e-commerce giants, but as it grew, expanded and evolved, it soon realized that having a 100% virtual presence is inadequate for enhancing the efficient accomplishment of its e-retail business. Some elements of brick-and-mortar physical presence would bolster Amazon’s capabilities to respond to the growing customer needs for efficient access and delivery of the required gifts, goods and groceries to Amazon Prime members.

To achieve that, Amazon first created its Prime Now. But this was not effective due to lack of effective physical brick-and-mortar presence that would facilitate logistical handling and management throughout several locations. This weakness was addressed by the acquisition of Whole Foods. Whole Foods was the disruptive operator in the global fresh foods and organic market. It had established its operations across various locations around the world. After its acquisition, Amazon Prime Now gained from Whole Foods’ extensive brick-and-mortar physical structures to support Amazon’s seamless logistical handling and managing of the flow of the distribution system from various stores to the final consumers. Following the introduction of Prime Now, Amazon was in competition with Whole Foods, but because Whole Foods was more established in the physical brick-and-mortar business world, it was better placed to disadvantage Amazon. Through strategic acquisition, Amazon managed to thwart such risks.

However, it is not only the case of Amazon-Whole Foods acquisition that illustrates how strategic acquisition is used for mitigating threats, but also the Disney-21st Century Fox Acquisition case. Following its creation, 21st Century Fox was one of the new movie and music streaming entertainment businesses fuelling the competition heat in the music and movie streaming industry. Combined with the disruptive emergence of Netflix, this caused threats that made Disney concerned about the future survival of its streaming business. In response, Disney acquired 21st Century Fox for $71.3 Billion. This bolstered the capabilities of Disney’s streaming and media businesses and entertainment services to effectively counter Netflix. Strategic assimilation is not only executed to improve the business’ capabilities, but also to gain access to the most lucrative market. When Foster’s Group was hindering SABMiller’s dominance in the Australian and Asia-Pacific market, SABMiller took the strategic action of acquiring and assimilating Foster’s Group in order to remain the dominant player in the Australian and Asia-Pacific market. Likewise, Uber had to acquire and assimilate Careem in 2019, in order to control and dominate the Middle East ride-hailing market. However, beneath the application of all these strategies is the development and use of the appropriate succession planning.

Strategic Succession Planners

Legendary historical businesses are strategic succession planners that invest enormously in the development and nurturing of their future business leaders. In that process, carefully planned and executed succession planning tends to be quite essential for influencing the evolution and transition of legendary historical businesses from one disruptive season to the other. Behind the adopted innovative strategies churning out an array of new products that bolster a firm’s adaptation to the evolving new trends, is the committed transformative leadership. It is the leaders who are instrumental for reading the situation and applying the appropriate strategies that aid the transfiguration and evolution of business from one century to the other. As Nestlé evolved from a family-owned business into a public limited company, it is its deployed leaders who were instrumental in the quests of ensuring its change and transformation from one period of disruptions to the other.

During problematic situations, it is its internally groomed business leaders that come up with solutions for addressing problems posing risks of failure. This enhances the mitigation of destabilizing problems to bolster a firm’s evolution and transition from one disruptive period to the next new seasons of relatively stable operations. It is the internally groomed CEOs that introduce more effective business turnaround strategies to avoid risks of decline, crisis or complete business failure and collapse. When IBM was about to face business hardship and extinction in the 1990s, it was Lou Gerstner, IBM’s CEO in the period between 1993 and 2002 who saved IBM from failure. Due to a higher focus on hardware at the expense of developing and selling new software programmes, IBM was facing problems, declining sales, low brand recognition and risks of business failure.

Coupled with its constraining bureaucratic culture affecting reforms, Lou Gerstner was introduced as the new CEO to effect the desired restructuring and reforms. Lou Gerstner, as the new IBM leader, introduced the business rescue plan requiring IBM to shift from just focusing on hardware to the creation of more appealing services and software. To achieve this, Lou Gerstner launched the “IBM Global Service” that would speed up research, innovation, development and sale of new software and IBM services. While advising IBM to adopt a customer-centric business operation, Lou Gerstner also restructured the business to streamline operations and reduce wastes and costs. IBM adopted more flat structures that improved the interface between various players in the IBM business sphere. Through such initiatives, IBM was reoriented from just focusing on hardware to internet and enterprise computing. This demonstrates how leadership can influence the evolution and transition of legendary historical businesses from one period of disruptions to the other. IBM was created and established on 16 June 1911 in Endicott, New York. Had it not been due to Lou Gerstner’s insight and transformative leadership, the 1990s’ situations depict some of the turbulent periods that could have caused IBM’s extinction.

Just like IBM, Apple was on the verge of bankruptcy and collapse, a decade after Steve Jobs had been ousted. In repentance, Steve Jobs was requested to return and lead Apple with new insights that would turn around Apple’s impending risks of failure. When Steve Jobs returned and took Apple’s leadership mantra in the period between 1993 and 2011, he introduced a business rescue plan agitating for the elimination of the less-profit-generating product lines so that Apple could just focus on a few profit-generating product lines. Steve Jobs also encouraged Apple to increase its investment in innovation. This influenced the creation of more disruptive products like iMac, iPod, iPhone and iPad. As these products emerged as the bestselling products around the world, it did not take long before Apple started rebounding back with vigour into the global consumer electronic segment’s leadership. Steve Jobs, inter alia, encouraged the adoption of a continuous innovation culture that unfolds together with the changes in consumer tastes and preferences. These were accompanied with the improvement of consumer experience as the tool for constantly branding Apple across the global market.

Reforms introduced by Steve Jobs prevented Apple from taking a downward trajectory into the path of bankruptcy and closure. It also continues to echo today as the unique innovative practices that continue to influence Apple’s business sustainability and evolution from one state of disrupted operations to the relatively more stable seasons. Yet as Apple was reeling from such awful business experience, Ford Motors, the previously vibrant business leader, was also experiencing declining sales due to declining product quality, rising operational costs and dwindling operating profit margin resulting from the increasingly bloated global business structure. Upon realizing the risks of these challenges plunging Ford Motors into failure, Alan Mulally, Ford’s CEO in the period between 2006 and 2014, introduced a business rescue plan dubbed “One Ford Plan”. “One Ford Plan” sought to eliminate structures so as to improve internal alignment and standardization of Ford Motors’ operations across all its global business structure. In addition to dealing with product quality issues, Ford Motors also streamlined product lines to focus on core profit-generating brands. Ford adopted collaborative teamwork as one big team. In effect, it quickly rebounded with rising sales and profitability.

By 2008, Ford Motors was one of the American businesses that did not seek for a government bailout during the 2008 financial crisis, because it was not affected by the crisis. This demonstrates how effective leadership is instrumental for saving legendary historical businesses from risks of failure during one disruptive period to the other. Effective leadership is the business brain and engine that drives the business’ evolution and transformation from one disruption of the century to the other. Just like Ford Motors, General Motors would have been dumped in the dustbin of history today, had it not been for Whitacre’s business rescue plan. The period between 2009 and 2010 can be remembered by General Motors as the year that it nearly fell into complete bankruptcy and extinction. However, immediately after General Motors’ placement under the US government administration, Whitacre, who was General Motors’ CEO at the time, intervened with a business rescue plan. Whitacre’s business rescue plan restructured General Motors to delete loss-making brands, enhance cost controls, operational efficiency and business focus. Whilst also flattening business structure to improve vertical and horizontal flow of information and collaboration, Whitacre released the bailout loan repayment schedules that would see the loan paid up ahead of schedule. Using Whitacre’s business rescue plan, General Motors was able to avoid failure and emerge stronger with the effect that by 2024/25 financial year, it has still remained one of the top performing legendary historical businesses generating $44 billion annual revenue and a net profit of $2.7 billion. These suggest how uniquely good leadership is part of the idiosyncratic resources that drive the evolution, change, transfiguration and transformation of historical legendary businesses from one century to another.

However, for such good outcomes to be realized, conceptualization and usage of the appropriate strategic succession plan is essential for nurturing and introducing a new set of leaders that influence the evolution of the business from one disruptive state to the other. Usage of a good strategic succession plan improves the development and future deployment of CEOs and leaders who understand the business better. Better understanding of the business implies that if disruptions occur, the CEO will easily know where to touch for the business to avoid risks of failure. Strategic succession planning is part of the internal strategic plan of the business. It is a proactive approach that enables the business identify and develop their probable future leaders in anticipation of taking over leadership when the existing leaders retire. It is an internal initiative, for the reason that a business cannot have a crop of new internal leaders developed during the succession plan implementation, and yet it still goes out fishing for a new CEO in case of a leadership vacuum. From the evaluation of the behaviours of legendary historical businesses like Johnson & Johnson, Ford, Toyota, BMW, Nestlé and Unilever, it is evident that although they are initiated to grow and become sustainable as family businesses, they have foresights that raise the “what if question”. The what if question is that—“if we are to thrive for long periods into the future, surpassing generations and generations into perpetuity, what do we need to do to achieve that as founding family business leaders?” Such a question has prompted the initiation and evolution of most legendary family businesses from the status of being completely family businesses to businesses that evolve to be managed and run by internally groomed family CEOs. These legendary historical businesses have often encouraged the transfer of leadership from family members to professionally trained business leaders. But as they do that, they identify and groom the potential candidates quite early.