By

Okanga Boniface

London, 31 June 2025

From Biden’s era, right into the beginning months of 2025, global trade boomed. US-China trade scooped $582.5 billion in 2024, just like UK-EU trade that fetched $976 billion. UK-US trade totaled $148.0 billion and the entire world of trade was happy (Office of the United States Trade Representative-USTR, 2025a). However, from nowhere, Donald Trump’s sudden introduction of a new tariff policy, hiking some tariffs as high as even 145% for China, caused, or is even still causing shocks that immediately paralyzed global trade. But even as global trade boomed, one of the things that most American politicians never told ordinary Americans was that America was getting almost nothing from the global trade deals reached with most of its major trading partners. When the US-China trade reached $582.5 billion in 2024, not so many Americans knew the US made a trade deficit of $295.4 billion, as it exported $143.5 billion worth of goods to China (USTR, 2025a). This compared quite badly with the whopping $438.9 billion worth of goods imported from China in 2024. When US-EU trade amounted to $976 billion in 2024, none of the officials in the Biden administration could also dare tell ordinary Americans that America exported just $370.2 billion worth of goods to the EU, as compared to $605.8 billion worth of imports from the EU. For US-UK trade that scored $148.0 billion, with $79.9 billion in exports to the UK and $68.1 billion in imports from the UK, the US generated a trade surplus of $11.9 billion (Office of the United States Trade Representative-USTR, 2025c).

Of course, the relatively higher tariffs are unfair. But even still, the US has serious trade deficits with most countries. This signifies that even if Donald Trump is blamed for introducing unreasonably higher tariffs, it seems it is only him who understood the statistical rationale compelling the introduction of higher tariffs. Some of the imported goods instigating the US’ increasing imports from other parts of the world may not alarm ordinary Americans, since they could be raw materials and inputs from various natural resources exploited from various parts of the world. Apart from Australia, and sometimes Africa and a few other countries that the US has a trade surplus with, it seems the US had and still has trade deficits with almost all the rest of its major global trading partners. It has trade deficits with most of the major economic blocs or powerful economies of the world.

Leaving alone the deficits with China and the EU, the United States has a serious trade deficit with Japan. In 2024, US-Japan trade reached $227.9 billion, but the US exported just $79.7 billion worth of goods to Japan as compared to imports from Japan that scooped $148.2 billion. This left the US with a trade deficit of $68.5 billion (Office of the United States Trade Representative-USTR, 2025d). While the demand for India’s precious stones, metals, jewelry, pharmaceutical products, organic chemicals and automobile parts, among others, surged in the past 10 years, as most US tech companies shifted their manufacturing base to India in a bid to gain from low-cost skilled labour, it did not take long before US-India trade reached $129.2 billion in 2024. This left the US with a trade deficit of $45.6 billion, as it exported just $41.8 billion worth of goods in contrast to $87.4 billion of imports from India. Of course, with the exception of China, Japan and the EU, one can understand the reason why these deficits have not been alarming. One reason is because most imports are actually American goods manufactured offshore in China. Therefore, whether or not America is experiencing a serious trade deficit with China, it does not bother most American businesses, for as long as they have scored the goals of producing their products at relatively lower costs that leave comfortable cost margins for competitive pricing. Secondly, given the relatively expensive American goods, caused by higher costs and standards of living that explain higher labour costs, most American consumers are not bothered if the American government makes a trade deficit, for as long as they are able to use cheaper imports from China to meet their various needs. Thirdly, some Americans are also not worried about trade deficits because most of the surging imports are essential inputs or raw materials which are important for making some other products. When the United States even had a trade deficit of $7.4 billion with Africa in 2024, as it exported $32.1 billion worth of goods against imports of $39.5 billion, Africans can only remain wondering if it is not the precious minerals that South Africa’s Gwede Mantashe lamented about that constituted the major US’ imports from Africa.

Of all the major US trade partners, it is only Australia which is among the good guys with which the US enjoys a trade surplus of $17.9 billion. In 2024, US-Australia trade reached $51.3 billion, as US’ exports to Australia amounted to $34.6 billion against its imports of $16.7 billion. Some of the imports are raw materials or inputs like semiconductors from China and Japan or crude oil and petroleum products, precious stones and metals, and agricultural products from Africa and South America. But still, decades and decades of US’ trade deficits with most of its global trade partners could have prompted the Donald Trump administration to take actions introducing tariffs that reshape the US’ global trade relationships to its advantage.

Whether or not the introduction of relatively higher tariffs is justifiable, the US’ introduction of very high tariffs has affected global trade. Even if some of the tariffs are being reviewed, it has still caused global business uncertainties that affect global trade. The new US’ tariff policy has distorted trade, affected sourcing and shipping decisions, as it also slowed global trade. Combined with the mutating effects of the Israel-Iran War which is disrupting the Middle East markets, as Qatar also closes its airspace, these imply that in the constantly evolving global markets, it is not only competitive actions of businesses that can turn to be devastating, but also actions by governments. In one way or another, government actions can precipitate outcomes that constrain or leverage trade. And in recent days, the constraining actions have been manifested in Donald Trump’s introduction of unreasonably higher tariffs against most of the United States’ previously good trading partners. Though the introduction of higher tariffs could be justified as a response to the rising trade deficits that the US has been grappling with for decades and decades, having a higher trade deficit does not necessarily mean the economy is doing badly. The country could be losing a lot of foreign exchange that affects the balance of payments.

But still, trade deficits can also arise from the surging domestic market demand that consumes all the domestically produced goods, leaving only a little or even nothing for export. This causes a shortage that demands more from the external markets. Rising trade deficits can be caused by the overall attractiveness of the domestic market, exhibiting higher economic productivity, lower unemployment rate and earnings increasing the purchasing power. This rising demand causes domestic shortages of goods to instigate the need for importation to fill the gap. In effect, the deficit the US is experiencing may not necessarily be associated with a poor or a weak economy.

Instead, the deficits could be arising from the US’ market’s attractiveness that consumes all that it produces domestically to demand more imports to fill the gap. On the international scale, the United States is one of the top ten countries with the highest GDP per capita. After Luxembourg with a GDP per capita of $145,826, Ireland with $143,179, Singapore with $138,545, Macao with $125,511 and Qatar with $118,148, it is the United the United States that takes up the sixth global position with a GDP per capita of $85,370. Higher GDP per capita implies the individuals in the country’s population are relatively wealthy, enjoying higher income levels, good life and often have adequate extra cash to spend on essentials and non-essentials. This increases the purchasing power to spur the increment of aggregate demand.

With higher aggregate demand, most businesses may be producing just for domestic consumption with little left for exports. Exporting also comes with costs. If the businesses can sell all their products locally, most of them would opt to focus on the local market. Higher domestic demand may stretch some businesses to the extent that they are unlikely to consider exporting unless it is necessitated by a surplus that cannot be sold locally. Yet as a country experiences relatively higher demand instigating rising prices, local consumers may avoid highly priced domestic products in favour of the imported cheaper alternatives. This is where the United States found itself with a constantly surging demand for Japanese, Chinese, South Korean, EU and Indian goods. “Made in America” goods are relatively more expensive as compared to the imported goods. Due to price advantages, even businesses that could have been producing and selling locally in the US market have turned to producing and importing from offshore operations into the US markets. All these mutate to contribute to a surge in trade deficits that the US experiences. As part of his reform programme dubbed “Make America Great Again”, Donald Trump, set to curb the dangerous impacts of such trends on the US economy by introducing a set of higher tariffs for selected imports from outside the United States.

Trump administration rationalizes the introduction of higher US tariffs as aimed at protecting the US domestic industries, while also spurring the increment of domestic investment, job creation and economic productivity and growth. The introduction of higher tariffs in 2025 was a continuation of Trump’s higher tariff policy that first surfaced in his first term of office in January 2018. In 2018, Trump administration imposed tariffs of 30-50% on washing machines and solar panels, 25% for steel, and 10% on aluminum. Though later reduced or being negotiated, Trump first introduced a 100% tariff on all electric vehicles from China. He also increased tariffs on lithium batteries, semiconductors, solar panels and steel and aluminum.

Even if the tariffs may induce the desired economic impacts, it seems to have instigated more chaos than it was intended. The extremely higher tariffs were criticized both in the US and abroad. In the United States, higher tariffs were interpreted to cause price increments and if not inflation. Tariffs are largely taxes charged on the designated goods imported from the other countries. Though they protect domestic businesses from external competition, those importing, even if the tariffs are higher, may opt to pass the higher taxes to the consumers in the form of higher prices. This causes sudden price increases as businesses importing certain goods seek to recover the cost paid as taxes for the imports. For the sake of lowering prices for essential goods and mitigating the risks of inflation, tariffs on certain goods are often set relatively lower. However, this was not the case with the Trump Administration. Yet as Trump’s new tariff policy was criticized as risking to instigate price increases, in the external world, Trump was criticized for alienating the US from the other countries. As China responded with double tariffs against the US goods, the Trump administration was accused of instigating trade wars. Trade wars refer to the economic approach where countries or different trading regions around the world use tariffs and other protectionist policies against each other to limit and prevent the inflow of imports from certain countries or regions considered as enemy states or regions. During the Cold War era, tariffs were part of the economic policies used as weapons against enemy states. However, when the World Trade Organisation (WTO) was created, it encouraged more free trade. It was from the campaigns and efforts by WTO that countries and different regions of the world started reducing and eliminating tariffs in order to encourage free trade and commerce between various nations.

Global Free Trade

Even before the WTO came into force, countries were already beginning to realize that stronger protection of domestic industries and usage of tariffs were not good for the economy. Tariffs insulated domestic industries from competition. This limited rivalrism that often drives businesses to be creative and innovative to survive. Decline in creativity and innovativeness affects quality. It also causes the exploitation of consumers using higher prices for low quality, since the country is not exposed to an array of the other better products being sold at relatively lower prices.

As different countries used tariffs as economic weapons against each other immediately after the World War II and during the Cold War, most countries had already realized how undesirable higher tariffs could be. Hence, when the World Trade Organisation came into effect on 1 January 1995, it did only little work to encourage countries to adopt free trade. Despite preventing the inflow of essential goods, countries had also realized the adoption of free trade to offer new market opportunities. As countries produce in excesses, global free trade was found to be essential for encouraging the sale of excess goods and services to the markets of shortages. This often increases the amount of foreign exchange earnings. It also catalyzes economic productivity and growth in the exporting countries.

Even if the country does not get a lot from global free trade, the little export earnings generated from global free trade often supplemented government revenues generated from the other sources to prevent overreliance on debt. Before recognising the economic values of free global trade, countries like China and India adopted stronger protectionist policies. They introduced higher tariffs against other countries, while also complicating foreign investment inflows. However, they soon realized stronger protectionism to affect foreign direct investment.

Reduction of foreign direct investments is significantly associated with declining economic productivity. This stagnates economic growth and employment creation. Of course, China still retains some stringent controls and regulatory barriers against foreign businesses’ investment in sectors like banking and finance, technology and defence. However, following its awful experience of the bad effects of using higher protectionist policies, China abandoned its centrally planned economy in favour of a free-market system. From the days of Deng Xiaoping’s Presidency in 1978, China adopted aggressive economic reforms dismantling its protectionist policy. It reduced or even eliminated some tariffs as the panacea for increasing export earnings, direct foreign investments, stimulating economic growth and gaining from the unique technologies that it would not easily access from its domestic market. China later joined the World Trade Organisation to advocate for free global trade.

While China’s elimination of tariffs and trade barriers was out of its own volition, India only got to realize the value of economic liberalization after it was forced by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to liberalize in 1991. For India to be bailed out from poor economic growth and a surging debt crisis, the IMF advised the Indian government to adopt economic liberalization eliminating or reducing tariffs, while also encouraging foreign direct investments. India deregulated and eliminated import quotas. When India introduced these reforms, it soon realized the value of free trade. India’s adoption of free trade policies spurred its economic rebound, growth and performance to emerge as one of the fastest growing economies of the world. From these positive experiences, China and India emerged as one of the aggressive advocates for free global trade.

Due to the enormous economic values that the global free trade generates, the encouragement of free trade and the formulation of free trade economic blocs emerged as the political tool that most countries used to encourage deregulation, free movement and trade across countries. Most countries realized that once political cooperation are forged, it can also be easier to encourage free trade that benefits all the members. In that process, India led the initiative for the establishment of ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations)-India Free Trade Agreement in 2010. The trade agreement sought to eliminate or reduce tariffs on 80% of goods traded by member countries, while also encouraging India’s access to Southeast Asian markets and supply chains.

In 2010, India also created India-South Korea Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement, 2011 India-Japan CEPA, 2022 India-UAE CEPA and 2022 India-Australia Economic Cooperation and Trade Agreement. Just like India, China also embarked on the campaign for global free trade. In addition to creating China-ASEAN Free Trade Area, it also established the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation that brought Russia, China, India, Pakistan and the other Central Asian countries as important trading partners. China has created a lot of trade partnerships with countries like Australia, New Zealand, South Korea, Switzerland and even the United States. As these countries embraced and evolved with free trade ideology, the United States, the longtime advocate for free trade, not only realized the opportunity to use free trade agreements and cooperation with the other countries as a political tool, but also as a neo-colonial instrument for controlling other countries.

The US introduced some trade agreements and cooperation that eliminated tariffs, even up to 95% on some goods. Such free trade agreements included USMCA (United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement), United States-South Korea Free Trade Agreement and the other free trade agreements with countries like Singapore, Australia and Chile. Other essential trade agreements signed by the United States’ governments included the 2022 Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity (IPEF), 2000 African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) and Trade and Investment Framework Agreements that link US with ASEAN countries. In the UK, the success of Brexit that could have affected UK’s enjoyment of free trade relationship with the European Union (EU) was mitigated by the creation of UK-EU Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) in 2021. Subject to rule of origin, TCA advocates for the elimination of tariffs and quotas on all goods traded between the UK and EU. Just like the US, the UK also has multitudes of trade agreements with the other countries. Such agreements encompass UK-Australia Free Trade Agreement, UK-Japan Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement, UK-Singapore Digital Economy Agreement and UK–Switzerland Mutual Recognition Agreement. However, as the world economy enjoyed free trade and thrived, Donald Trump decided to pour cold water on the whole initiative by introducing unreasonably higher trade tariffs.

Higher trade tariffs not only frustrated global trade, but also caused confusion, uncertainties and unpredictability that still continue to hamper the seamless flow of global trade. Instead of encouraging free trade, Trump imposed 50% tariffs on EU imports. It was subsequently reduced to 20% and then 10% up to 8 July 2025 as discussions for an amicable position are reached. For China, Trump introduced 145% tariffs on all imports from China. This prompted China to retaliate with higher tariffs that threatened to disrupt the lucrative US-China global trade. Following domestic pressure for businesses that rely on Chinese imports as inputs, the United States and China have agreed to waive-off all higher tariffs’ increments except the so called Trump’s Liberation Day baseline tariffs of 10% for all imports into the United States.

For the UK, Trump and Keir Starmer, the UK Prime Minister, recently signed an order confirming the US-UK Tariff Deal at 10% tariff for most UK exports into the US. But a lot of restrictions still persist as some sort of quotas are introduced to limit the UK car exports to the US to just 100,000 cars per annum for 10% tariff. This signifies after the 100,000 cars, higher tariffs would apply. In the deal, the position of steel and aluminium is not clarified to cause more confusion and uncertainties for the UK steel and aluminium exporters as well as the US steel and aluminium users like those in the auto manufacturing and building construction sectors.

Regarding Canada and Mexico, the US introduced 25% tariffs on imports from the two countries and a 10% levy on Canadian energy. As Canada retaliated with 25% tariffs for all vehicles imported from the United States, domestic pressure from the US car-makers prompted Trump to initiate trade talks with Canada. But of late, during the G7 Summit in Canada, Trump did not insinuate any sign of relenting. Instead, he lamented that Canada may still have to pay higher tariffs. Yet as the United States increased tariffs for all these countries, it introduced a 25% levy on all imported steel and aluminium, cars, computers and smartphones, even including smartphones manufactured by Apple outside the United States, and films that faced 100% tariffs’ increment. However, as Trump increased tariffs, the United States was the first victim of the undesirable effects of tariffs’ increments. Given the past US tariff increment blunders, which Trump is also aware of, the mutating unintended consequences of tariff increments instigate questions as to whether the ratiocination is “Make America Great Again” or “Upside Down Again”.

“Make America Great Again” or “Upside Down Again”

In the United States, prices increased to cause a slump in demand. Price increases affected manufacturing businesses in the sectors like automobile engineering, electronics and pharmaceutical industries that rely on a lot of inputs like steel, aluminium, semiconductors and other materials imported from the other parts of the world. Yet as the prices of inputs increased, it also affected the accessibility of the lower income consumers to essential goods like medical drugs. Increases in prices affected demand that in turn reduced the US market attractiveness. As profitability and productivity reduced, most businesses also started to downsize by laying off some workers. In the long run, positive effects on increased employment creation may emerge.

But for now and so far, this has caused job losses in the first few months after Donald Trump’s announcement of tariffs’ increments. As tariffs’ increments close out some of the essential cheaper inputs, most US businesses revealed declining price competitiveness in the global market. Expensive exports from the US may deter businesses and consumers from the other parts of the world from using “Made in America” products. In the long run, this can affect market competitiveness, performance and sustainability of some US firms.

To mitigate such risks, some US firms may consider retaining the existing offshore manufacturing facilities in low-cost manufacturing locations like China, Vietnam, Mexico and India. Such manufacturing facilities may be producing relatively cheaper products for the competitive international markets as the local US domestic manufacturing facilities produce for the local US markets. Yet as the US market experiences such undesirable consequences, good trade relationships and agreements are often used by the US government not only as an economic tool for controlling trade, but also as a political tool for controlling and influencing other countries. When some African countries like Gabon, Uganda, Central African Republic, Sudan and Niger failed to heed to the US government demands to improve adherence to the requisite democratic and human rights principles, it did not take long before they were suspended by the US government from AGOA (African Growth and Opportunity Act).

Now that the sudden tariffs’ hikes are causing the likely formation of a new world economic order like BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China & South Africa) that threatens to invite even Iran and North Korea, it implies in the near future, the US may not be able to use some of its trade agreements as political tools for influencing policies in the other countries or regions. Besides such undesirable unintended consequences of Donald Trump’s tariffs’ hikes, the global supply chains of most global businesses that relied on China for inputs and other intermediate goods were also disrupted. This mutated with the uncertainties arising from various retaliations against the new US tariffs’ increments to affect global trade.

As countries retaliated and Trump paused the implementation of the new tariff policy up to August 2025, pending further review and discussions, it caused uncertainties. In the bid to restore predictability and certainties in global trade, China, Canada, France, Germany and the UK all jumped in to individually negotiate and strike a deal for fair inter-trade tariff policies. But as they did that, global businesses engaged in either exporting or importing goods to or from America to the EU, Canada, China or any other parts of the world faced uncertainties. They were and are still not aware what the tariffs deal would produce. Unsure of whether fair, good or bad, most of the global business operators could not make decisions on whether to proceed with purchases from China, EU or Canada. This uncertainty affected global trade.

Though the US has so far reached tariff deals with the UK and China, a lot of uncertainties and unpredictability still linger for as long as Donald Trump remains the president of the United States. Donald Trump holds the view that the United States can perform better to reverse its increasingly alarming trade deficits if the US domestic businesses and manufacturers are protected. However, he seems not to realize that ever since China evolved into the second most powerful economy of the world, a lot has changed. Countries are increasingly investing in innovation that improves not only product quality, but also affordability of pricing. In contrast, America is a highly structured capitalist market with higher GDP per capita and higher standard and cost of living. This leaves the labour market demanding more and more wages, thereby increasing production costs.

Even if most American businesses are increasingly deploying robotics and a higher degree of automation, this renders it difficult for the US manufacturers to lower costs and prices to outcompete some of the best low-cost producers of the world. Such economic conditions affect cost competitiveness. Poor innovativeness is the other driver of poor cost management. Japanese firms as well as businesses from China, India and Vietnam focus on evaluating and reducing the quantity of materials used in the manufacturing of various products.

In contrast, American manufacturing firms by virtue of their extravagant culture never explore much into the innovative strategies for reducing the quantity and costs used in the manufacturing of various items. This results in the production of relatively more expensive products that cannot even sell well in the US domestic market. Hence, the surge in trade deficits where the US imports more than it sells, just because its consumers are searching and purchasing cheaper products from the other markets of the world. In addition to market volatility as the stock markets reacted negatively to the new tariff policy announcements and retaliations, the IMF (International Monetary Fund) and World Bank unleashed similar statistical views indicating that the global economic growth had slowed as most global businesses paused movements of goods across various global supply chain systems and waited for the uncertainties to subside.

Before the introduction of the new US tariff policy, the world was already struggling with the uncertainties arising from geopolitical tensions created by Russia’s unrelenting attacks on Ukraine. After Zelensky’s mistreatment at the White House sent signals that Donald Trump would be taking a pro-Russian position, the EU was pondering with how to deal with Putin if US support under Trump becomes quite minimal. But before the EU could process how to deal with such issues, Donald Trump even worsened that confusion by announcing new tariff increments that would reshape the nature of global trade and relationships. Countries retaliated in various ways to US’ announcement of tariff increase. This exacerbated tensions and confusion that the global governments were already grappling with. Now that Israel’s sudden attack of Iran’s nuclear sites threatens to metamorphose into a protracted full-scale war, one wonders if the likes of Canada and EU countries that are still reeling from the confusion created by Trump’s sudden tariff hikes will become viable US allies if Iran becomes problematic for Israel to require the support of US and its allies.

Even if Trump’s sudden tariffs’ hikes have generated a lot of controversies and criticisms, his controversial tariff policy is not the first one in the history of US economic system. In the 1930s, the US introduced higher tariffs under its Smoot-Hawley Tariff to protect American manufacturers and farmers. In the quest to prevent the US economy from sliding into an economic recession leading to the Great Depression of the 1930s, the US government increased tariffs on over 20,000 various goods to protect the US manufacturers and farmers. But this tariff increment and the move towards protectionism were not well received around the world as Canada and most European countries retaliated with tariff increments. This affected exports and global trade to worsen US’ economic recession and instigate the 1930s’ Great Economic Depression.

As if no lesson was learned in the 1930s, in the 1980s, the US was yet again engulfed in another tariff war with Japan. To curb Japan’s faster economic growth and stronger utilization of the US market as the revenue-generating pool, the US government imposed tariffs on Japanese electronics and autos. The US also threatened to do more. But Japan relented and negotiated their way out by choosing to undertake long-term investments in the US market to avoid tariffs, improve its growth import-substitution industries and contribute to the US economic growth and development.

After some years of relative global trade stability, in 2018–2020, the US, while citing unfair trade practices and intellectual property theft, imposed tariffs on Chinese imports worth $550 billion. China retaliated by imposing tariffs on about $185 billion worth of imports from the US. Noting that the US-China War was affecting global trade, both China and the US government relented by negotiating a trade deal. It was the same set of tariff policies that Trump revised and re-introduced in April, 2025. But as these tariffs are introduced, most global businesses have often come up with various innovative ways of avoiding tariffs or the complications, uncertainties, and operational disruptions associated with complying with stringent tariff policies.

US Global Businesses’ Tactics for Tariffs’ Avoidance

In the event of tariff hikes, some of the tactics used by some of the US global businesses that manufacture and import various goods from China into the US have often entailed the use of:

-

- Global Supply Chain Reconfiguration

-

- Reshoring or Nearshoring

-

- Product Re-Configuration, Redesign and Re-Classification

-

- Country-of-Origin Alteration and Transshipment

-

- Advocacy and Lobbying the US Government

-

- Passing Tariff Increments to Consumers

-

- Strategic Alliances and Partnerships with Firms in Less Tariff-Affected Countries

Details of how they apply each of these tactics are evaluated as follows.

Global Supply Chain Reconfiguration

In the event of a tariffs war or prolonged political hostilities, supply chain reconfiguration is one of the strategies that most global businesses use to change and restructure their sourcing or manufacturing operations from the politically sensitive or tariffs-affected countries to relatively risk-free countries. It entails the abandonment and shifting of sourcing and manufacturing activities from the countries of higher risks to the low-risk manufacturing destinations. Leaving alone tariff wars, in the event of changes in political dynamics creating prolonged hostilities between two countries like the case of South Korea and North Korea, US and North Korea, Russia and the European Union or Israel and Iran, most global businesses often avoid getting entangled in the unfolding political hostilities by shifting the manufacturing activities from the affected countries to the countries of lower operational risks.

When China rebounded from its economic recessions of the 1970s to begin experiencing unstoppable growth, most of the global business operators soon realized China to offer lower-cost manufacturing advantages. China was increasingly creating and delivering relatively cheaper products into the global market. As Chinese companies increasingly gained price advantages in the increasingly competitive global market, most global operators were prompted to ask questions and explore what Chinese companies do to gain such unique cost advantages. Combined with the capabilities of Chinese companies to create and deliver highly attractive products, most global businesses also questioned the creativity advantages enjoyed by Chinese companies. In response, China was found to have the highest population of qualified scientists and engineers. This higher investment in science education increased science graduates to lower the overall operational costs.

China was also found to have a higher population of relatively well-educated people. Because of limited employment opportunities to take up all the qualified science graduates, most qualified science graduates were willing to work for relatively lower salaries and wages. Combined with China’s business operational philosophy that emphasizes the use of simple solutions for more complex problems, China emerged as one of the uniquely low-cost manufacturing destinations of the world. This lured most multinational corporations, even from the United States, to consider investing in China.

To gain from low-cost manufacturing capabilities, multitudes of American-based global businesses shifted or opened new manufacturing plants in China. This created a new supply chain configuration where most goods were moving from the central global manufacturing location in China or the “Factory of the World” and getting distributed to various markets around the world. But the introduction of such new global supply chain and manufacturing strategies was soon disrupted by Trump’s tariffs’ increments.

If the US business was not establishing a manufacturing plant in China, it would instead engage the best global suppliers based in China. But when Trump increased tariffs on imports flowing from other countries into the US, it was China which was the main target of the US’ tariff increments. To avoid higher tariffs that meant higher operational costs and reduced price competitiveness in the US and other global markets, most US retailers, manufacturers, and tech-companies shifted their manufacturing facilities away from China to Vietnam, Thailand, Mexico, or India. Prior to tariff hikes, Apple used Pegatron and Foxconn as its major partners in China to manufacture AirPods, iPhones and other devices. Following the increment of tariffs, Apple requested GoerTek and Luxshare to shift AirPods’ production from China to Vietnam. From 2020, the production of iPhone 11 and SE models were also shifted to India. Just like Apple, Nike that had relied on Chinese factories to make its sports shoes and wear, also shifted its orders to Vietnam, Thailand, and Indonesia, after Donald Trump increased tariffs on footwear, apparel, and textiles.

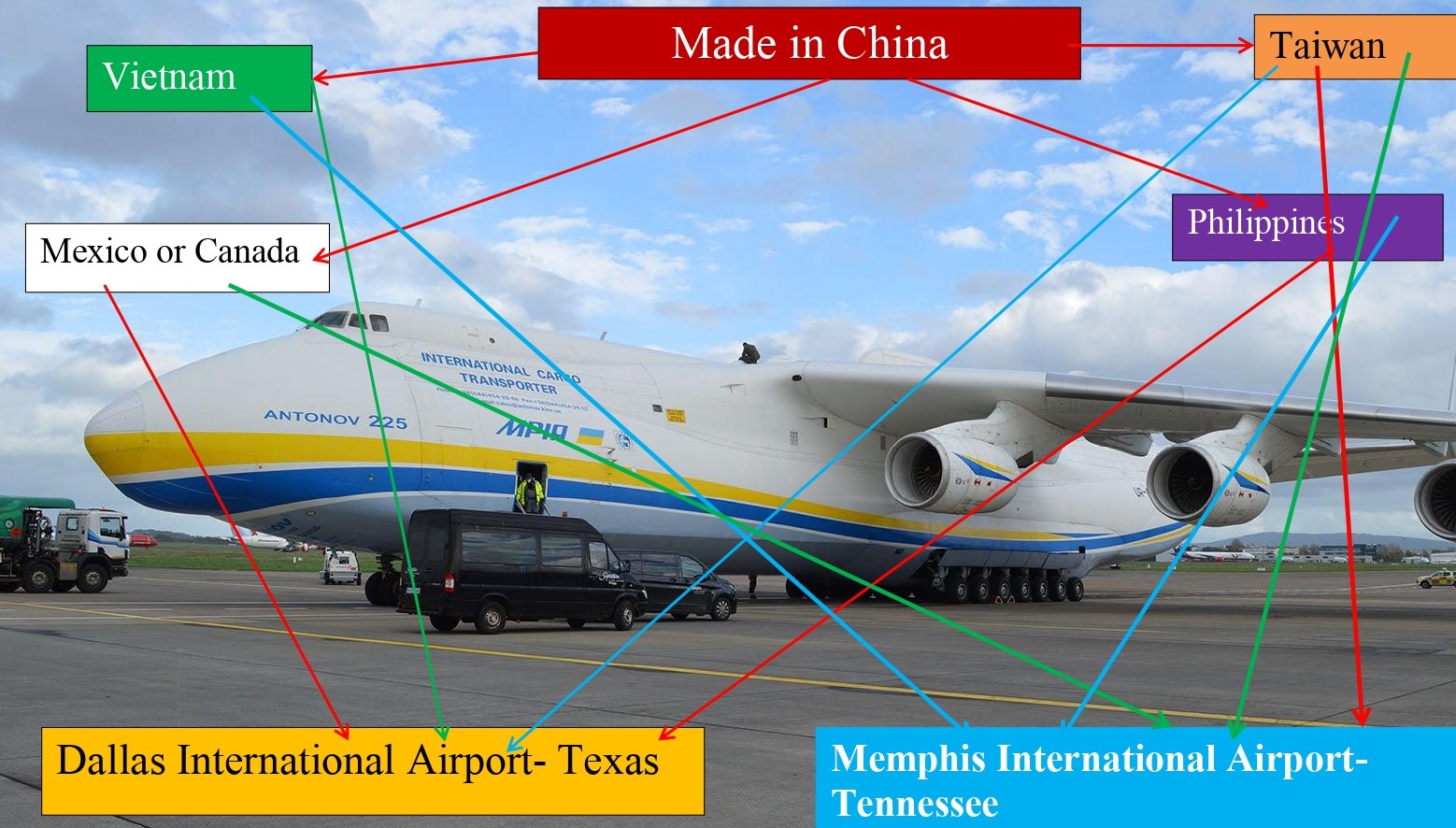

HP and Dell shifted 30% of notebook production to Taiwan, the Philippines, and Vietnam when Trump imposed tariffs on smartphones, laptops, and tablets. Levi Strauss & Co. moved from China to Egypt, Turkey, and Bangladesh. To mitigate higher costs arising from the increment of tariffs on steel and aluminium components, General Motors abandoned the Chinese suppliers in favour of the steel and aluminium manufacturers in Mexico and Canada. These cases illustrate how global business operators can go about shifting and reconfiguring their manufacturing activities and supply chain operations in order to avoid higher tariffs. Though these enable global businesses avoid tariffs, during the initial stages, it still disrupts the smooth flow of activities and profitability. If global businesses are not reconfiguring their global supply chain operations, they may opt for reshoring or nearshoring.

Reshoring or Nearshoring

As a result of tariffs, most global businesses may shift production away from the high tariffs’-affected countries to either home production or to the establishment of their production plants near home markets. In that process, reshoring is a strategic process of relocating the production plant from the countries affected by the increment of tariffs to the domestic market. When the introduction of a new policy increasing tariffs is accompanied by the introduction of economic packages for the domestic businesses, the option is usually to shift production home in order to gain from the new policies.

Instead of relocating the production plant to the home country, the nearshoring strategy relocates the manufacturing plant to a nearby foreign country which is considered to have better manufacturing conditions and resources. When Donald Trump increased US tariffs on all the imports from the other countries, most US global businesses applied reshoring to relocate their manufacturing plants from China to the US market or nearshoring strategies to relocate their manufacturing plants from China to Mexico, Canada or Central America. Reshoring and nearshoring enable global businesses avoid higher tariffs by shifting away from countries being targeted by high tariffs. It also enables global businesses reduce costs and minimise risks of failure as smooth operation is affected by constant quests of having to comply with the higher tariff policies. Sometimes to achieve such business advantages, the affected US global businesses producing and importing from China have often used strategic alliances or partnerships with the firms in the countries not affected by tariff increments.

Through strategic alliances and partnerships, the US firms are able to utilize production and manufacturing facilities of the firms in less tariffs’ affected countries like Vietnam, Thailand, Taiwan, and India. However, usage of reshoring or nearshoring may not be a viable strategy in certain cases for that in a democratic country like the US, changes in tariffs tend to vary with the changes of governments. When a particular political party takes over government, it may favour or limit free global trade. For that reason, applying nearshoring or reshoring to relocate the manufacturing plant away from the tariff-affected country may not be a sound business strategy. Later governments can easily waive or significantly reduce tariffs in the affected country to render the country more attractive again.

Due to higher rivalry to attain global economic supremacy, it seems the United States will always introduce more hostile trade policies against China. However, still relocating just because a particular ruling party may uphold higher tariffs for five or ten years may not be a sound business decision. In the first term, Donald Trump targeted China with higher tariffs. During his second term, Trump targeted China plus other countries like Canada and Mexico. This implies if a US global business had nearshored to Mexico and Canada, the nearshoring would not have any good business value. The nearshoring business would still be affected by the higher tariffs that it attempted to avoid by relocating from China to Mexico or Canada.

Though these imply nearshoring or reshoring is not worth undertaking sometimes, during global actions undertaken to avoid higher-tariff-affected countries, nearshoring or reshoring is often still the global manufacturing strategy that most global business operators pursue. After the increment of tariffs on all Chinese furniture imports, La-Z-Boy, a global player in the furniture manufacturing industry, reinvested in the US to increase the scale of its Mississippi and Tennessee manufacturing facilities. It also closed its China production facility and shifted its furniture production to its Monterrey factory in Mexico. Likewise, General Motors also applied nearshoring and reshoring by relocating its steel/aluminum production from China to nearby countries like Mexico and Canada. It also increased investment and strengthened its Michigan, Ohio and Texas steel/aluminum production plants to improve US market access whilst also avoiding tariff barriers. However, for New Balance, the US manufacturer of shoes, athletics wear and sneakers, the option was not closing its Chinese plants. Instead of closing its shoe manufacturing plants in China and other countries, it just increased the scale of its US shoe manufacturing in Maine and Massachusetts.

Through such initiatives, the US production would serve New Balance’s larger US market, as the China production plants would serve the demands in the other parts of the world like Europe, Australia and Asia. Just like Stanley Black & Decker, the maker of hand tools and Red Wing Shoes, Hasbro, the US toys maker reduced its Chinese manufacturing activities by 30%, while also opening new manufacturing plants in Mexico and India. Yet as global businesses are not reshoring or nearshoring, they may opt to use product re-configuration, redesign and re-classification.

Product Re-Configuration, Redesign and Re-Classification

Product re-engineering, redesign and re-classification is the strategic process of altering or modifying product components or ingredients with the motive of making them become other products that qualify for lower tariffs or no tariff classifications. If a product cannot pass through customs to enable the reaping of higher profit margins, the global business may change a few things to enable it comply with no tariff or lower tariff classifications. While products are redesigned, modified or bundled, they qualify for lower tariffs or no tariffs at all. This improves the capability of the business to continue operating without disrupting their Chinese operations using nearshoring or reshoring strategies.

When Trump introduced higher tariffs for Made-in-China empty plastic containers, Gojo Industries, which is one of the US global businesses operating from China, bundled the product by putting in sanitizers. Without the sanitizers inside, the plastic containers attracted higher tariffs. But when the plastic containers are used for packaging sanitizers, the entire bundle becomes classified as sanitizers that do not attract any tariff. Such initiative leaves the global business avoiding tariffs without disrupting their global supply chain operational systems or engaging in illegal activities. After the introduction of tariffs on wearable electronics like watches from China, Apple redesigned its Apple Watch to not only become a watch, but also a medical device that monitors health fitness during exercises or jogging, blood pressure and heartbeat for those with blood pressure and heart problems. For such reason, Apple Watch was reclassified as a medical device that does not attract any tariff.

When new tariffs were introduced, complex toys bundled together with the other electronic components and batteries attracted higher tariffs as compared to if toys are separated from batteries. In effect, most of the US-based global businesses importing toys from China had to separate toys from batteries and other separate electronics, so as to qualify for lower tariffs. For prepared or preserved foods, the food importers from China had to alter a few ingredients for canned garlic and mushrooms for them to fall below prepared or preserved foods’ thresholds.

To respond to higher tariffs for 100% synthetic clothing, US apparel manufacturers operating from China and importing into the US had to alter the fabric components by including 4% spandex and 96% polyester. Yet as some businesses engaged in such practices, GoPro, a manufacturer of electronics and cameras, adopted the product re-engineering strategy of eliminating and reducing components used in certain products. Even if the paid tariffs are relatively higher, price increments would not be required to offset the paid tariffs. This leaves the business remaining competitive even after paying higher tariffs. However, such a strategy would require high levels of creativity and innovativeness to ensure the product components are altered without undermining its core functionality and operational efficiency and effectiveness.

If the global business operator is not engaging in such initiatives, it may opt for aggressive cost-reduction and efficiency improvement initiatives. These may entail the introduction of higher levels of automation, process re-engineering eliminating or merging some processes, downsizing and consolidating facilities’ usage. These are often combined with the use of robotics and artificial intelligence. Such aggressive cost-cutting initiatives lower costs to improve a business’ ability to pay up tariffs and still continue operating without increasing prices to affect price competitiveness. In a bid to offset higher tariffs on imported parts, electronics and steel from China, Caterpillar introduced leaner inventory management. It also adopted automation and digitization to reduce wastes and costs that would enable it pay up tariffs and remain operating profitably without increasing prices. Likewise, to respond to higher tariffs for steel, Whirlpool eliminated some product lines to focus only on the high revenue-generating product lines. It also automated its supply chain operations while eliminating or reducing unnecessary marketing and business administration expenditures.

For Hasbro, the manufacturer of toys, it had to restructure and streamline workforce, consolidate warehouse operations and distributions in North America and re-evaluate its packaging to reduce weight by using lighter materials, so as to reduce shipping space on ships and costs. These imply instead of using nearshoring and reshoring from China to US or other locations, the global business operator can just adopt aggressive cost-cutting strategies to reduce costs and improve or retain the existing net profit margins without increasing prices. Apart from the use of such strategies or product re-configuration, redesign and re-classification, some US global business operators from China often use Country-of-Origin Alteration and Transshipment.

Country-of-Origin Alteration and Transshipment

In the quest to avoid hostile tariff increments by the United States against China, some of the global manufacturing businesses operating in China have often opted for the country-of-origin alteration and transshipment as part of the strategies for getting the goods to the US market. In that process, most global businesses ship their products or components to third countries where the components are assembled into final products prior to re-exporting to the United States. In some cases, products requiring higher tariffs’ payments are often directly shipped to third countries and relabeled as made in the third country prior to re-exporting to the United States.

Transshipment and country-of-origin alteration are fraudulent and illegal activities. If caught, it can attract hefty fines that erode the value of its usage as a viable strategy for avoiding paying higher tariffs to the US customs. Despite such risks, most of the global businesses operating from China and in various other countries often still use such a strategy. To avoid paying higher tariffs to enter the US market, some of the Chinese-made steel is often shipped to Malaysia as a country that does not attract higher US tariffs and then labelled as “Made in Malaysia” and re-exported to the US. When such vices were discovered by the US authorities, a combined effort of the Malaysian authorities and the US Department of Commerce was put in place to continuously monitor, track and curb the illegal import and re-export of Chinese steel disguised as the Malaysian-made steel. In addition to the steel case, Chinese plywood and furniture were also re-routed to the US via Vietnam, where the furniture and plywood were relabeled as made in Vietnam prior to re-exporting to the US market. Though the vice continued for some time, the US Customs and Border Protection soon discovered the illegality and urged Vietnam to tighten rules on Country-of-Origin Certification or else all Vietnam exports would be completely banned in the United States.

Following the increasing oversight of the US Customs and Border Protection, Hanwha Q CELLS, which is one of the South Korean global businesses, was also found to have engaged in a series of solar panels’ re-export to the US via South Korea. As the solar panels passed through South Korea, they were relabeled as made in South Korea. South Korean exports do not attract higher tariffs at the US Customs and Border Protection. Likewise, when exporting to the US, toys and consumer goods made in China were also re-routed via Thailand and the Philippines until stringent country-of-origin verification stopped the vice in 2020.

In addition to using country-of-origin alteration and transshipment, other global businesses often use advanced shipments and inventory hoarding. As news of potential tariff hikes or risks of tariff retaliations and wars are anticipated, some global businesses tend to import and hoard the required products in larger quantities. Though this can increase the inventory holding costs and overwhelm customs clearing activities at borders, it still enables global businesses avoid sudden profitability declines. It enables the global business avoid sudden profitability declines or stock shortage as it ponders how to deal with the effects of the new tariff hikes in the long run. Before Trump could impose 10%-25% tariffs on imported electronics from China, Apple and its contracted suppliers had to import extremely larger quantities of MacBooks, iPhones and other various forms of consumer electronics.

Even if this increased holding costs, it still enabled Apple to have time to discern how to react to tariff hikes by, for instance, shifting its manufacturing activities from China to Vietnam. During the same 2018 year, Walmart, in anticipation of tariff hikes, imported and hoarded extremely larger quantities of furniture, electronics and toys from China before tariffs could set in. As Walmart engaged in such activities, the US-based global business operators like Caterpillar and Ford also imported and hoarded a lot of steel and aluminum products to mitigate the risks of supply chain disruptions in the short run.

Just like Ford and Caterpillar, US businesses operating in the clean energy sector also had to import and hoard a lot of Solar Photovoltaic (PV) panels before Trump could impose a tariff of 30% in 2018. If some of the US-based global businesses are not using such a strategy, they may opt to apply for tariff exemptions. However, tariff exemptions are often offered only for rare products which are not easily available in the US market. To make its Model 3, Tesla applied for tariff exemption on control brain used in Chinese-made Electric Vehicles. Realizing that it would not have any supplies outside China, General Electric also applied for tariff exemptions for parts like x-ray systems and circuit boards.

Apple applied for exemptions from tariffs on stainless steel enclosures, power supplies and circuit boards that are used as parts in Mac Pro. The manufacturers of semiconductors requested for exemption from tariffs on fluorinated compounds and rare earths imported from China. If the US-based global businesses are not passing the higher tariffs to consumers in the form of higher prices, they may advocate and lobby the government to reduce or waive certain tariffs for certain unique agricultural, pharmaceutical or electronic products. When the EU and US used several retaliatory tariffs against each other after the WTO found Airbus and Boeing to have been illegally subsidized, Boeing lobbied the Aerospace Industries Association to intervene. Aerospace Industries Association convinced the US and EU governments to de-escalate tariff wars and tensions that would affect the seamless flow of activities in the global commercial aviation supply chain system. To become competitive in the global market, the American National Pork Producers Council and the American Soybean Association not only lobbied the US government to address trade disputes limiting agricultural exports, but also to increase subsidies for agricultural production.

In a nutshell, all these imply as governments hike tariffs or engage in tariff wars to distort global trade, most global businesses also become quite creative and innovative on how to keep the global supply chain system operational and profitable at the same time.

Citation: Okanga, B. (2025). Trump’s Tariff Policy: Global Trade and US Global Businesses’ Operational Tactics for Avoiding Tariffs. London: Cloud Analytika.

Okanga is a Professor of Innovation Strategy and the R&D Research Associate at The Business School, Edinburgh Napier University-Scotland.

Further Readings

Alfaro, L., & Chor, D. (2023). Global supply chains: The looming “great reallocation” (NBER Working Paper No. 31661). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w31661/w31661.pdf

Clarke, J. (2025). What tariffs has Trump announced and why? London: British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC). https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cn93e12rypgo

Collins, G. (2025). Apple shifts supply chain by diversifying production. Supply Chain Digital. https://supplychaindigital.com/procurement/apple-pivots-to-india-with-expected-us-22bn-output

Conerly, B. (2023). Near-shoring: Can manufacturing move from China to Mexico? Forbes. https://www.forbes.com

Glas, K. (2022). China tariffs are working in nearshoring manufacturing. Just Style. https://www.just-style.com/comment/china-tariffs-are-working-in-nearshoring-manufacturing/

Lal, D. (1995). India and China: Contrasts in economic liberalization? World Development, 23(9), 1475–1494. https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-750X(95)00074-3

Ma, H., & Ning, J. (2024). The return of protectionism: Prospects for Sino-US trade relations in the wake of the trade war. China Economic Quarterly International, 4(3), 182–211.

Moser, H. (2021). Biden vs. Trump on reshoring: A review, and a critique. IndustryWeek. https://www.industryweek.com/the-economy/trade/article/21154656/biden-vs-trump-on-reshoring-a-review-and-a-critique

Nurullah, G., & Serif, D. (2023). US–China economic rivalry and the reshoring of global supply chains. The Chinese Journal of International Politics, 16(1), 61–83. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjip/poac022

Office of the United States Trade Representative-USTR. (2025a). The People’s Republic of China: China trade summary. Washington, DC: USTR. https://ustr.gov/countries-regions/china-mongolia-taiwan/peoples-republic-china

Office of the United States Trade Representative-USTR. (2025b). European Union trade summary. Washington, DC: USTR. https://ustr.gov/countries-regions/europe-middle-east/europe/european-union

Office of the United States Trade Representative-USTR. (2025c). United Kingdom trade summary. Washington, DC: USTR. https://ustr.gov/countries-regions/europe-middle-east/europe/united-kingdom

Office of the United States Trade Representative-USTR. (2025d). Japan trade & investment summary. Washington, DC: USTR. https://ustr.gov/countries-regions/japan-korea-apec/japan

Pettypiece, S. (2025). New data shows U.S. manufacturing productivity decreased in April. NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/economics/trumps-tariffs-are-causing-pain-us-manufacturers-rcna204786

Sharma, A. (2024). Apple’s production strategy in Vietnam. Vietnam Briefing. https://www.vietnam-briefing.com/news/apples-production-strategy-in-vietnam.html/

South China Morning Post. (2025). Apple eyes India, Vietnam to replace China as its key manufacturer. https://www.scmp.com

Spiegel, R. (2022). Biden pushes hard for reshoring in State of the Union. Design News. https://www.designnews.com/industry/biden-pushes-hard-for-reshoring-in-state-of-the-union

Srinivasan, T. N. (1988). Economic liberalization in China and India: Issues and an analytical framework. In Chinese Economic Reform: How Far, How Fast? (pp. 137–153). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-587045-0.50014-9

Sutherland, B. (2025). GM’s $4 billion spending push shows why reshoring is so hard. Bloomberg. https://www.bloomberg.com

Thomson Reuters Tax and Accounting. (2025). History of U.S. tariffs and why it matters today. https://tax.thomsonreuters.com/blog/history-of-u-s-tariffs

VanHulle, L. (2025). GM weighs tariffs, EV demand, factory flexibility as it moves some production to U.S. Automotive News. https://www.autonews.com

York, E., & Durante, A. (2025). Trump tariffs: Tracking the economic impact of the Trump trade war. Tax Foundation. https://taxfoundation.org/trump-tariffs-tracking-economic-impact-trade-war

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.